Modern identity politics is often denigrated; depicted as an irrational mass shouting defiantly about their experiences; a moment of politics that erases the good old fashion posturing of parliamentary debate. While identity politics, like all politics, operates in oppositional or even sometimes fascistic ways, it remains unclear it is theoretically unsound. This piece seeks to locate the root of modern identity politics. That root is born out of bearing witness, giving an account of oneself. This is best explored through an engagement with Adornian pessmism. When Adorno claimed, amongst the ruins of Europe and the aftermath of WWII, that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” he in essence began to question, in effect, whether bearing witness could have a political function.[1] This essay shows how the acts of bearing witness to the horrors of the holocaust ran counter to Adorno’s pessimism. Adorno’s negative comments are set up in relation to a debate about exteriority and critique, an issue that can be illuminated by the use of outward gaze in modernist painting. This constitutes the first digression. With this background, a discussion of the poetry of Paul Celan as a poetry that bears witness to the horrors of the holocaust ensues. It is through Paul Celan’s poetry that we begin to see how bearing witness is political and thus runs against Adorno’s pessmism. This is the second digression. Finally Gregor Von Rezzori’s book Memoirs of an Anti-Semite is discussed in relation to Celan’s poetry. This is the third digression. In this comparison of the poetry of Paul Celan and Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, we can discover a political use for bearing witness that undoes Adorno’s glum proposition and allows us to see how bearing witness, giving an account, serves a proper political function.

I.

“Think more than you paint”

John Russell To Tom Roberts, circa 1885

In the introduction to Foucault’s The Order of Things, he provides a careful analysis of Velasquez’s painting Las Meninas (Maids of Honour).

Foucault notes the outward gaze of the subjects of the painting – the various maids of honour, dwarves, courtiers, and Velasquez himself all gaze out from within the painting, their sight drawn to where any viewer of the painting would be, their gaze drawn to the exteriority of the painting. However what would be a radical gesture is turned back in itself, as at the centre of the painting there is another image: two figures, presumably contained within a mirror. Indeed Foucault identifies this as a mirror, and the objects within as King Philip IV and his wife Mariana.[2] Located then, in the centre of the painting, is the figure of the sovereign. The outward gazes from the various figures within the painting curve back into the painting itself, as what they are gazing at is given representation itself, the exteriority is reinscribed as the interiority of the painting. The viewer who stumbles across the painting remains a spectator, watching the seen unfold as an objective witness. Indeed, Las Meninas is part of an era of Baroque paintings that includes Rubens magisterial paintings, an era when form, style and representation all strived for objective representation. This is the same era Vermeer attempts to properly capture the effects of light, it is the era where even paintings of biblical scenes are highly detailed and extraordinarily lifelike.

The attempt to create hyperrealistic paintings always requires a self-contained universe: the scenes themselves are supposed to have happened in a curtailed space. This is why in Las Meninas the gaze of the subjects of the painting turns back into the painting and Velasquez gives representation to what captures the gaze of Las Meninas. To do otherwise would be the blur the boundary between viewer and painting, to erase the status of the viewer as objective witness to a scene, and with it to undo the striving of objectivity for which the works, intellectual or artistic, of the 17th century oftenaspired.

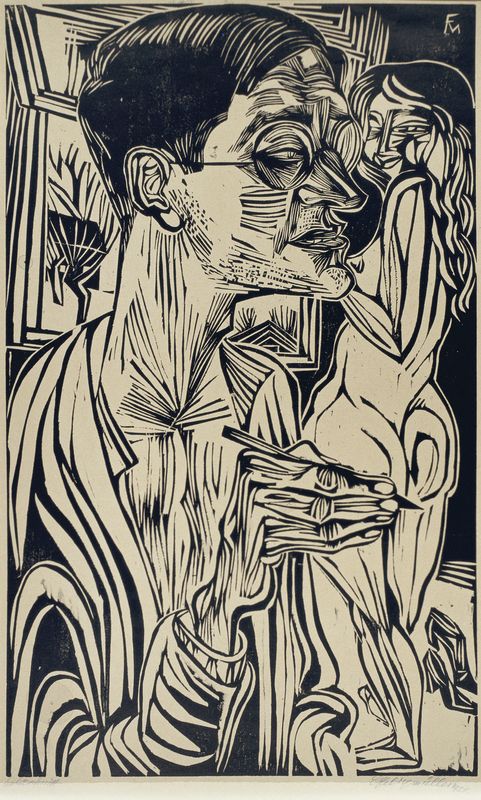

This point about objectivity may seem obscure, but can be emphasised by way of a comparison. Going forward almost 300 years from Las Meninas, consider Conrad Felixmuller’s 1924 Myself, drawing (Self-Portrait with Nude) (see figure2).

Here we are presented with something similar to Las Meninas – an image of artist in the midst of his work, while the gaze of the subject of the painting is outwards. However, while Velasquez subverts this gaze back into the painting, Conrad Felixmuller leaves it unreflected. The Nude in the background of Felixmuller’s woodcut gazes out from the painting, past the image of Felixmuller gazing into his easel and into the viewer.

What space does the viewer occupy in Felixmuller’s work? Traditionally one would say that they are in the place of a mirror, but this misses something given by the title of the work. Myself, Drawing (Self-Portrait with Nude) blurs a set of distinctions. Presumably the figure of Felixmuller in the foreground is of him engaged in painting the nude, his gaze is directed away from the viewer, from the location of a mirror that would make this self-portrait possible.

What moment, then, has the viewer stumbled upon? Felixmuller composing the nude, and nothing else? In this case what is the nude looking back and out at? The ambiguity here breaks the self-containment of the painting. The viewer is not spectator, not objective witness to a displayed scene. They become part of the action, a figure gazed at by the subject of the painting. The viewer is still a viewer, and certainly a witness, but the kind of witness they have become is a vastly different one: with no high place left they are drawn into the image. The privileged outside viewer becomes a subjective viewer, drawn into the scene, no longer external to it.

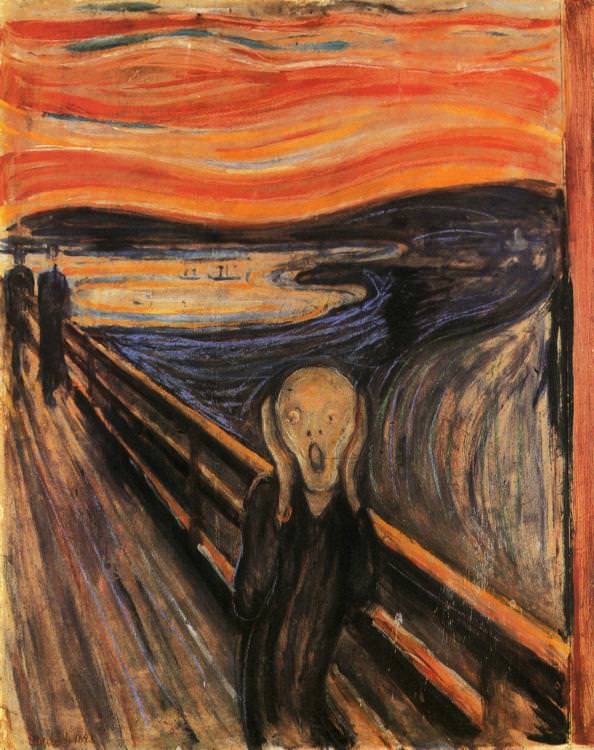

The 300 years that separate Velasquez from Felixmuller, separate not only a multitude of artistic movements, but vast transitions of society. Felixmuller himself is poised a few decades shy of the advent of post modernism. However, as he is a modernist one can find traces of the themes of postmodernism in his work, as Jameson has done with Edvard Munch.[3] For Jameson, Munch’s The Scream (see figure 3) “deconstructs its own aesthetic of expression,” that it is it undoes the tenets of modernism around which it is constructed.

The Scream dates from 1893. Thus one can imagine that by 1924, this deconstruction of aesthetic expression Munch set out upon was being pushed even further. So even though Felixmuller’s work predates the advent of postmodernism and with it the full blown discourse around the idea of a non-objective witness, the tenets and idea of postmodernism where already in circulation. Felixmuller’s work is part of the arrival of this postmodern theme of the non-objective witness, part of the theme of a loss of exteriority. This theme, as we shall see, plays a crucial rule in the post-WWII poetry of Paul Celan.

II.

“The Splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass” Theodor Adorno[4]

Let us return to the quote of Adorno’s with which we began. When he declared that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” he was hinting towards this changed status of the witness that one can see when Las Meninas is compared to Myself, Drawing (Self-Portrait with Nude). Adorno’s claim, expounded in his essay ‘Cultural Criticism and Society’, is that participation in the kind of culture that produced Auschwitz is itself barbaric. When we attempt to critique a society by reproducing the cultural monuments of that society, we render our criticism obscure and impotent. The implication of such claim requires, if we are to hold on to our beliefs in emancipation, progress and the ability to resist fascism, an objective viewpoint. The cultural critic must stand in a position of exteriority to society to be able to gaze in to its depths and critique it effectively. This is the ideal of much of enlightenment era reason as coolanddetached.

However the problem is a topographical one. Where, exactly is this position of exteriority to society? How does one reflect on a society without reproducing any of its cultural monuments? If this position doesn’t exist, if every act of critique is also an act of implication, how are we to provide a critique of society? Poetry after Auschwitz maybe barbaric, but politics would appear impossible.

In Paul Celan’s poetry one finds the suggestions of a refutation to Adorno’s cynicism. Celan’s poetry often deals explicitly with the Shoah (the Jewish term for the Holocaust). One of Celan’s key figures in relation to this is the figure of the witness. In the final stanza of Paul Celan’s poem ‘Aschemglorie Hinter’, translated simply as ‘Ashglory’ by Pierre Joris, he says:[5]

Noone

bears witness for the

witness

Though ‘Ashglory’ itself is free from any direct mention of it, the spectre of the holocaust hides behind the poem’s grim intensity. For Celan the mere act of writing in German was to invoke and grapple with the spectre of the holocaust, to engage in an attempt to resurrect a language killed by Nazism.[6] Celan himself is, throughout his poems, bearing witness to the horrors of the Holocaust.[7]

However when Celan claims that no-one bears witness for the witness, there is a more profound point to be made. Consider the origins of the word ‘witness’, etymologically linked to the word ‘testify’. In Latin, the word for witness, testis is linked to the word for a third person, terstis.[8] Thus the witness is a third person, a supplement to the two-person dispute.

This idea of a witness underpins Las Meninas, but is broken by Myself, Drawing. Suddenly the witness becomes embroiled, is no longer outside the dispute. They may remain a third, but they are a third in a three person dispute, no longer an arbiter. When Celan writes that no-one bears witness for the witness, the question arise for why the witness would need a witness. However if the witness is itself involved in the dispute, it no long functions as an arbiter, no longer objective. This stanza of Celan presents the same problem latent in Adorno’s quip.

However Celan’s oeuvre works against the pessimism of Adorno. Part of Celan’s project is to bear witness for a new life.[9] Thus, while he affirms the new state of affairs, of the witness as subjectivity, from within this subjectivity it may be possible to build a new world. How this is exactly done remains unclear in Celan, obfuscated by the fact that, as Jorris’ claims, we are still learning how to read Celan.[10] Understanding Celan’s project as an attempt to resurrect the German language in the aftermath of WWII and the holocaust provides the insight in how Celan’s work operates against Adorno’s maxim: language is the cultural monument par excellence. After WWII, after the Shoah, German is a language render impotent, if not dead. It is the tongue in which hideous crimes have been committed. Celan takes German, his mother tongue but not his only fluent tongue, and uses it to forge a series of testaments to horrors begone. However Celan does not just forge testament to horrors past, he points towards a future. Consider his poem Threadsuns:[11]

above the grayblack wastes.

A tree –

high thought

grasps the light tone: there are

still songs to sing beyond

mankind.

Passing over the post-humanist intentions for a moment, here is a poem in which Celan leaves the grayblack wastes towards light and song. The imagery here is hopeful and in a dual move Celan seeks to point towards a brighter future for man by articulating hope in a dead language. This move is nothing less than to revitalise a dead language. If one can revitalise a language and turn it to give account of the horror it itself bore out that those not close off the sphere of the possible, then one has reinscribed resistance into language itself which is culture’s base form. Celan’s commitment to using the language of the holocaust (German) in his poetry displays his view that from within the cultural monuments that produce barbarity one can undo the callousness of history. One can bring poetry back from the realm of barbarity and use it to build a new world from the ashes of the old.

III.

“We’re all there, We’re all guilty”

Fugazi, Suggestion

It is possible to object that Celan occupies a special status as a victim of the holocaust. Celan, as a victim, is outside the cultural logic. The idea of the victim as the site of exteriority from which the proper critique of society can be enacted is problematic. Emancipation becomes the namesake of the precarious. This would reduce our position to a limp imitation of Marxism. Our privileged class, capable of emancipation, becomes the class of victims. The question then becomes the following: can one, if they are guilty, if they are implicated in the horrors of the world, bear witness and engage in building a new world out of the ashes of the old?

It, in some ways, is crucial that the answer to the above question is yes. One can find this account in Gregor Von Rezzori’s Memoirs of An Anti-Semite. Rezzori’s book bears witness to enabling antisemitism of pre-WWII Europe from the perspective of an antisemite. Rezzori is, indeed, guilty of being absorbed in the cultural monuments that produced the holocaust in way that it is possible to exonerate Paul Celan from.

As Hannah Arendt was often at pains to show the horrors of the holocaust were rarely orchestrated by perverts or deviants. Instead many of those involved, even at high order levels, were by all accounts ordinary (perhaps their crimes was not being extraordinary). This is in fact the corner stone of her “banality of evil” thesis: ordinary people are capable of heinous crimes.[12] Heinrich Himmler, who was the leader of the SS and responsible for many of the horrors of the holocaust, was, according to Arendt, in fact nothing more than then the normal family man par excellence, a perfect bourgoise man who was loyal to his wife and concerned with the future of his children (as an aside, it is reported that Himmler helped proposed the final solution in part because shooting Jews en masse was too upsetting for his precious Totenkopfverbände).[13]

What Rezzori’s book bears witness to is how antisemitism was a banality in the lead up to the holocaust. Rezzori covers five episodes in his novel. The first three capture the microcosm of anti-semitism: boyish cruelty in Skushno (the first tale of five), public humiliation of a Jewish sexual partner in ‘Youth’, and private humiliation of a nonsexual Jewish partner in ‘Lowringer’s Boarding House’. Throughout Rezzori’s narrator, a pale imitation of him, pleads innocent and surprise when his cruelty backfires. However, as Hitchens in his review of Memoirs of an Anti-Semite points out, the proper and older Gregor Von Rezzori, the author, is always poking his head out from behind the novel. When what is suppose to a youthful and very Romanian von Rezzori describes a room as full of “Chagallian poetry” or identifies a kupat kerem kayemet” [a collection box for the redemption of palenstine] one senses the presence of an older more worldly von Rezzori.[14] This appearance of the author of the text underpins the often innocent tone in which the narrator reacts, it is often offset by an ironic distance in which one understands the cruelty at play.

These microcosmic moments of antisemitism unfold in the large historical arch in the fourth episode,’ ‘Troth’. ‘Troth’ is the first story where Nazism and Hitler, always distance or background objects, begin to rear their ugly heads. Suddenly the narrator finds himself amidst a procession in the otherwise abandoned streets of Vienna: “In blocks that in their disciplined compactness seemed made of cast iron, people marched by the thousands, men only, in total silence. The morbid, rhythmic stamping of their feet hung like a gigantic swinging cord in the silence that had fallen on Vienna.”[15] This is Rezzori’s description of the march in favour of the Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria in 1938, it brings back the political context to what was otherwise a superficially apolitical narration. ‘Troth’ is by far the most grim of the five episodes that make up Memoirs of an Anti-Semite and its grimness sets out to highlight the horrors of cultural complicity.

In its narrative that relegates antisemitism to being part of the everyday, Rezzori’s book bears witness to the banality of racism. By doing so it critiques society and the individual and offers Gregor’s mild complicity and guilt as an account of the horrors of silence and lack of judgement proper. Rezzori’s book becomes a testament to how our latent views cause our complicity in horrors and it is in this way critical. Being so deeply within the system and still being able to produce a critique of it, a critique the also serves as a warning, dismantles the Adornian pessimism found in his pithy phrase “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.”

IV.

“We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old”

Solidarity Forever

What then do we bear witness to? In our world where all spectators are also part of the game, we cannot stand outside the canvas to judge. We must judge from within the system. Both Celan and Rezzori bear witness, and turn that bearing of witness into part of a process to provide critique and ways forward. In this reaction to the horrors of WWII and the holocaust, horrors that changed the face of European civilisation, we see a response to the old problem of critique from the inside. By bearing witness, as victim or perpetrator one begins the process of critique anew.

Here, at long last, we find the roots of modern identity politics, in which the effort is to bring the masses of persecuted to bear witness to the horrors they have faced – horrors perpetuated by a society that is at once exploitative, sexist, racist, transphobic, and homophobic; a society that provides moments of justice and yet, more often then not, enforces injustice. To bear witness to the horrors of society is to once again, after Auschwitz, write poetry that is no longer barbaric.

Celan and Rezzori’s works don’t themselves signify the kind of blatant art as cultural criticism that Adorno may have had in mind, but the represent the very ability to reclaim art as a form of critique, even in conditions where society has produced barbarity. This point is important, we do not choose the society we are born into, and we do not, not at least for a while, choose the kind of socialisation we are given. We must use the tools we are given to build a new world. If one is to claim that this is impossible, one is to claim that a new world is unobtainable. We must form critique out of the cultural monuments we have. If this new world is born out of the ruinous parts of the old then so be it. Celan and Rezzori’s work testify to this possibility. In a world where the German language had been rendered dead, or at least impotent, Celan and Rezzori offered nothing less than an attempt to revitalise it through bearing witness to the horrors it had wrought.