Those who follow International Relations might have notice the curious rise of the “Thucydides Trap” as the vogue concept among leaders. Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has dropped the reference on numerous occasions at international summits abroad.[1] It sounds so sophisticated, so sexy, so suave as an explanation for understanding contemporary great power relations that its popularity is understandable. Aside from demonstrating his erudite knowledge of the Greek Classics, Turnbull is saying that relations between dominant powers and rising powers (see US and China) are tense because intentions are uncertain and defensive capabilities hold the potential for aggressive strikes. These power relations inevitably send the system into conflict. While this textbook response is certainly a gripping and sensational narrative of US-China relations, is also not particularly authentic.

The phrase ‘Thucydides Trap’ actually has very little to do with Thucydides at all. It only began to see usage in the last 15 years and was popularised in part due to Professor Graham Allison of Harvard. This essay will attempt to provide a fuller account of how presenting the ‘Thucydides Trap’ as justification for the enduring nature of Realist ideals in two millennia of international statecraft is revisionist at best. At worst, it is intellectually disingenuous to portray Thucydides’ methodology, conception of power, and framework of agency as identical to the neorealist framework which pervades strategic decision making today. While Thucydides does share some common elements with Realism today, it is the differences that merit some critical introspection from policy makers and academics alike.

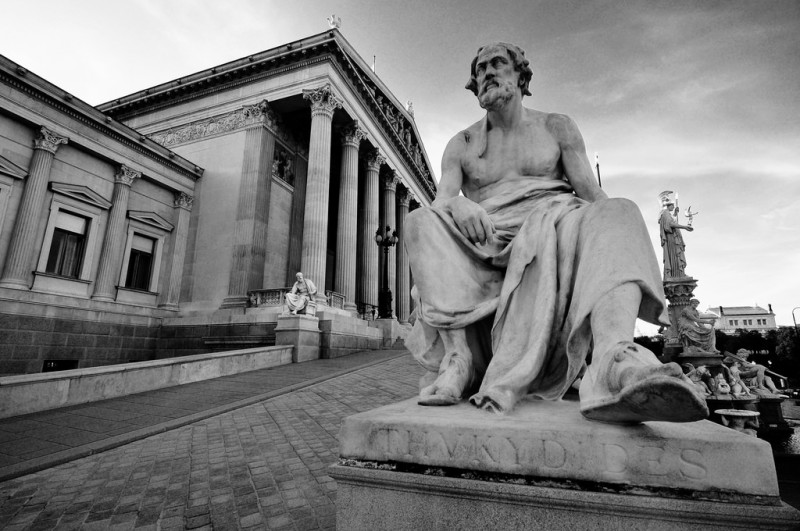

Here I will make the claim that Thucydides occupies a troubled position both as the most iconic and the least understood figure in International Relations. Advocates of realist statecraft from Machiavelli to Kissinger claim to have read Thucydides, yet few provide more than a superficial snapshot. This should come as no surprise. Anyone who has ever engaged in the act of conversation should be familiar with the set of miraculous coincidences which occur with each fraught exchange. First, one hopes that both parties will speak the same language. Second, with luck, that both can understand the logical relationships being established during the conversation. Finally, both sides are required to share the contextual knowledge needed to make the implications of the content readily apparent. Only then can conversation follow. Most likely, far fewer conversations happen in reality than we like to believe. By this benchmark, Thucydides is that one who is always at the edge of conversation but never directly engaged in it.

If it is true that Thucydides is as central to Political Realism as so many seem to think, then it is worth having a hard look at these roots. Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War was written in the years after the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) between Athens and Sparta and attempts to give a full account of the events leading up to, during, and after the war. The central theme is apparent in Thucydides’ oft quoted explanation for the cause of conflict between the two city-states:

“What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.”

Thucydides (Book 1, section 23)

Putting aside the finer points of Greek translation, the quote has been used by Realism as the historical example par excellence of how political inquiry should be conducted. First, it is from this quote that the modern methodology of positivism in Realism is justified. Certain forces are enduring laws of behaviour, and the purpose of political science is to uncover the forces which inevitably lead to certain outcomes. Second, the key determinant behind behaviour in international politics is power. Third, it establishes the primacy of the state in determining international politics. To each of these observations in turn, I want to elaborate on how Thucydides presents a more multifaceted account of politics than the popular presentation prevalent today acknowledges.

Politics is both a Science and an Art

On the first issue of methodology, Thucydides is rightly judged to be prescient for anticipating the analytical shift in International Relations towards a more rigorous scientific approach. In the History, Thucydides employs a methodological approach which emphasises the analytical interpretation of empirical evidence. Thucydides assembles eyewitness accounts, personal observations, and recorded speeches to understand the Peloponnesian War, which are then organised into a single definitive account. Thucydides argues that interpretative selectivity is necessary to progress beyond being a simple chronicler of history to one who understands history. This methodology departs from earlier historians such as Herodotus, who would often present several different explanations of events, leaving the final judgement of validity up to the reader. In this sense, Thucydides is more of a political scientist than a mere chronicler of historical events: he aims to find the patterns which govern political behaviour.

While Thucydides has certain similarities with contemporary positivist accounts of politics, these similarities go only so far. There are epistemological difficulties in ascertaining this knowledge. Historical events are complex and historical remembrance is the result of both imperfect memories and biased observers (1:22). Thucydides consequently employs a degree of abstraction throughout the History to better emphasise the essential character of the actors as he sees it. Here, Thucydides engages with the art of statecraft. Athens and Sparta can be thought of as a stylised representation of the politics of order versus the politics of energy.[2] Thucydides’ intention is likely to capture the interaction of not just Athens or Sparta as historical entities but rather as a generalised portrait of conflict from which valid lessons for any future Athenianesque state or Spartanesque states may be drawn. Thucydides deals not just with the science of politics but also ventures into the art of statecraft through examining the psychology and leadership of both Athens and Sparta.

The History also contains strong themes of indeterminism and frequently acknowledges the role that chance plays in shaping outcomes. Thucydides’ personal experiences as a young general offer a good illustration. The Greek word ‘etyche’, “it so happened”, is used to explain the success of the Spartan general Brasidas who benefitted from being in the right place at the right time when he managed to triumph over his Athenian opposition.[3] Despite exercising sound judgement, Thucydides the general was subsequently dismissed from military office and exiled for twenty years for his failure to defend the city of Amphipolis (5:26). In statecraft, unexpected changes in fortune are the rule rather than the exception. While the theoretical practise of political inquiry in the abstract should be characterised by careful observation and empirical analysis, the actual practise of politics in the History assumes an ontological reality significantly clouded by uncertainty. Politics is as much determined by the whims of fate and chance as by those quantifiable forces governing the system. Thucydides would be fundamentally cautious about definitive statements that something will happen as the result of something else because it had happened before.

The logic of power is not necessarily rational

For Thucydides, the central concern of states is survival and continued capacity for autonomous agency. Dominion over others is strategically desirable because it allows a state to both enhance its own power and prestige while limiting the capacity of rivals to gain a similar advantage. Thucydides understands power in quantifiable and empirical terms as a function of the state capacity to project force. There is something recognisably modern and realist about this. This is evidenced by Thucydides’ statement about how it was the rise of an ascendant Athenian power threatening the established Spartan hegemony as the status quo power which sparked the war (1:23). This theory of security emphasises the importance of relative power since to weaken the enemy is also to grow one’s relative strength. The result is the classic security dilemma where the very process of power accumulation by states in search of security induces opposition from other states who feel threatened by expansionism. Sparta is driven to fight Athens because Athens would do the same in Sparta’s position.[4] This vision of the international system suggests that politics should essentially aim to study the measurable features of material power.

Power however operates in unpredictable ways. Consider the rich soil paradox, where the poverty of the Attica region of Athens actually endowed it with relative political stability (1:2). Refugees fleeing instability migrated to Athens and formed a prosperous society based on trade. It is by leveraging their merchant and naval power that Athens’ rise to imperial power was enabled.[5] Here, it is curious that it was poverty which initially created the conditions possible for eventual rise. It is through a mix of both circumstance and ‘tyche’ that the city of Athens reached its position of relative power and prestige. Consequently, while many material factors have the potential to contribute to power they do not do so in a deterministic way. There are important qualitative differences in the ways in which power can manifest itself, and it is these qualitative details which matter for history. One cannot aggregate power in crude quantitative terms without losing meaning in the process.

Perhaps the most important part of the picture, however, is that Thucydides also gives significant due to the immaterial elements of statecraft. The important second half of Thucydides’ famous statement reminds us that it is not Athenian power alone which determines behaviour in an anarchic international system, but rather the “fear which this caused in Sparta” (1:23). The behavioural psychology of states cannot be ignored. Thucydides makes it clear that it is the interaction between fear and power that shapes state behaviour.[6] How this fear will manifest is not consistent across all states. At the funeral oration Pericles claims that “there is a great difference between us and our opponents, in our attitude towards military security” (1:49). In other words, the security dilemma derives from power relations, but fear acts as the intervening variable. This is an important distinction for the practise of statecraft in that it suggests that intangible and unquantifiable factors like psychology have the potential to shape political reality.

The nature of the state is determined by individuals

Finally, although Thucydides does give a great deal of attention to the agency of the state in driving statecraft, this is different from the ahistorical and acultural conception of sovereign states used in contemporary realist analysis. This is illustrated by the way in which national characters are constructed in the History. Thucydides uses the concept of national character as an explanation for the respective tendencies and instincts of Sparta and Athens.[7] The national character of Athens has a tendency towards boldness and speed but also a rashness of action. Sparta has a tendency towards prudence and caution but also a slowness and cowardice (1:66-71). Athens and Sparta are distinct agents with distinct personalities. Thucydides does not necessarily suggest that either character is the superior character since the traits each have their associated strengths and weaknesses.[8] Sometimes risky action brings rewards and sometimes it brings disaster. This implies that not only is the perspective of the other state different, but such difference has real implications for outcomes.

At the core of Thucydides is the observation that politics is driven by human action. International relations cannot ignore or reduce the human individuals involved. Thucydides makes an interesting distinction between the differences in attitude toward being wronged by an equal compared to being wronged by a superior (1:77). The consequential outcome of being wronged is equally significant from an objective perspective, but the perceptions involved in feeling wronged means that it is not the same from subjective interpretation. The example of Brasidas illustrates the importance of an individual’s effort in swaying human sentiments in negotiating surrender (4:114-123). It is only through a process of cajoling, persuasion, and debate that Brasidas manages to leverage material force to achieve the surrender of Athenian allies. This suggests that while the logic of power operates in a rational and amoral manner, the perception of power is not easily separated from issues of justice and fairness.

This means that political behaviour is liable to change over time depending on circumstances and context. This is partly determined by the temperament of the individual and partly by previous learned experiences. The boldness and rashness that typically characterised the Athenian attitude becomes fearful, prudent, and urgent following their catastrophic defeat in Sicily. Weaker city-states soon turn on Athens emboldened by their perception of Athenian weakness (8:1-2). The perception of present reality is one of constrained rationality at best. Individuals employ heuristic processes that are prone to moments of both over-optimism and over-pessimism.[9] That which is demanded of political leadership, then, is to weigh up the appropriate action, based not merely on convenient laws of human behaviour, but to undertake inconvenient and difficult decisions in order to shape desirable outcomes through their own actions. For Thucydides, statecraft requires both the rational capacity to accurately assess situations as they really are, as well as the emotional capacity to inspire, persuade, or intimidate as the situation demands.

Pandora ’s Box contains evil but also hope

I mentioned earlier that Hobbes had a particular fascination for Thucydides.[10] In a way, Hobbes’ translation of the History says less about Thucydides and more about Hobbes. Hobbes’ translation of Thucydides echoes many of the phrases, themes, and ideas which would later go into Hobbes’ own work of political theory, The Leviathan. Thucydides is a work that provides a rich tapestry of events and characters for the reader to draw upon, and within this richness it is each for each reader to project ideas and values of their own. A difficulty in the objective reading of any kind of work is the interpretive selectivity inherent in research. The interpretation of outcomes suffers from a confirmation bias where observers are most liable to see that for which they are looking. Theoretical and empirical beliefs held by an observer can manifest easily when making sense of complex events, which distorts findings and conclusions. If Thucydides lies at the roots of Realism, it is worth asking how much of the original lessons from the History are still remembered today.

Realists who believe state power can explain everything about International Relations soon start to see power everywhere and in everything. That which goes unnoticed, however, includes the myriad instances in which such is not the case. Because human inquiry necessarily simplifies the messiness of history, the result is a discounting of everything which does not fit the expected model. An overzealous search for the rules of political behaviour has a tendency to blindly ignore the exceptions. Eventually, such preconceptions lead to the creation of self-fulfilling prophecies in the practice of statecraft. If states act according the paradigm of self-help and fear, changes in their own behaviour will induce systemic changes on the collective practices and attitudes of others. Independent of whatever the initial ‘true’ nature of those actors was like, the assumption of motivation through fear will quickly lead other states to adopt positions and strategies which justify those initial assumptions.

Understood in this way, Thucydides shares much more in common with the classical tradition of Realism of the E.H. Carr flavour than contemporary Structural Realism, due to their shared appreciation for the importance of human action in shaping outcomes. The triumph of power politics over morality during the Melian Dialogue debate found in the History was not a statement on the eternal nature of international politics, but simply one instance in which the advocates of unrestrained power won out over the advocates of cooperation. The lesson for the contemporary practitioner of statecraft is simple. The ‘Thucydides Trap’ is only a trap so long as human imagination cannot look beyond imminent confrontation. Many times in the History, it is leadership both good and bad that determines the key events in history both noble and tragic.

Far from uncovering the underlying laws which govern human behaviour, the project of Realism has its roots on shaky foundation. This does not make Realism intrinsically bad. It may be that the best system we have to guard against those brutes wielding naked power is to become more fearsome brutes ourselves. It is however disingenuous to claim that such a system is natural and inevitable. Realism will only continue to reflect reality so long as we continue to adhere to such a paradigm. In the same way that an unwanted suitor hears what they want to hear despite apparent polite rejections of their amorous affection, so too do Realists like Hobbes and Kissinger read whatever they want to read from Thucydides. Spare a moment of thought for Thucydides, unable to protest the vigorous advances of overeager Realists. Spare a moment of thought for us, those who must live with the consequences.

Bibliography

[1] See http://www.afr.com/opinion/columnists/laura-tingle/malcolm-turnbulls-terror-response-needs-less-thucydides-and-more-broadmeadows-20151126-gl8icn; http://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/beijing-must-beware-the-thucydides-trap/news-story/8e784ec686a3b35f982661076c1a2661?nk=ef690e93bf7371b96104ab71074424cf-1461992112; and http://www.smh.com.au/world/america-is-stronger-than-ever-malcolm-turnbull-20160118-gm8qo3.html

[2] Kateb, “Thucydides’s History: A Manual of Statecraft,” 484.

[3] Thomas Heilke, “Realism, narrative, and happenstance: Thucydides’ tale of Brasidas,” in American Political Science Review, vol. 98, no. 01 (2004) 125.

[4] Kateb, “Thucydides’s History: A Manual of Statecraft,” 496-497.

[5] Foster, Thucydides, Pericles, and Periclean Imperialism, 12-14.

[6] Perez Zagorin, Thucydides: An Introduction for the Common Reader (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 44-46.

[7] See Luginbill, Thucydides on War and National Character; Crane,”The Fear and Pursuit of Risk,” 227.

[8] Felix M. Wassermann, “The voice of Sparta in Thucydides,”in Classical Journal (1964) 289.

[9] Gregory Crane,”The Fear and Pursuit of Risk: Corinth on Athens, Sparta and the Peloponnesians (Thucydides 1.68-71, 120-121),” in Transactions of the American Philological Association (Scholars Press, 1992) 230-233

[10] Hobbes’ translation of the famous phrase goes “And the truest quarrel, though least in speech, I conceive to be the growth of the Athenian power; which putting the Lacedæmonians into fear necessitated the war” http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/771