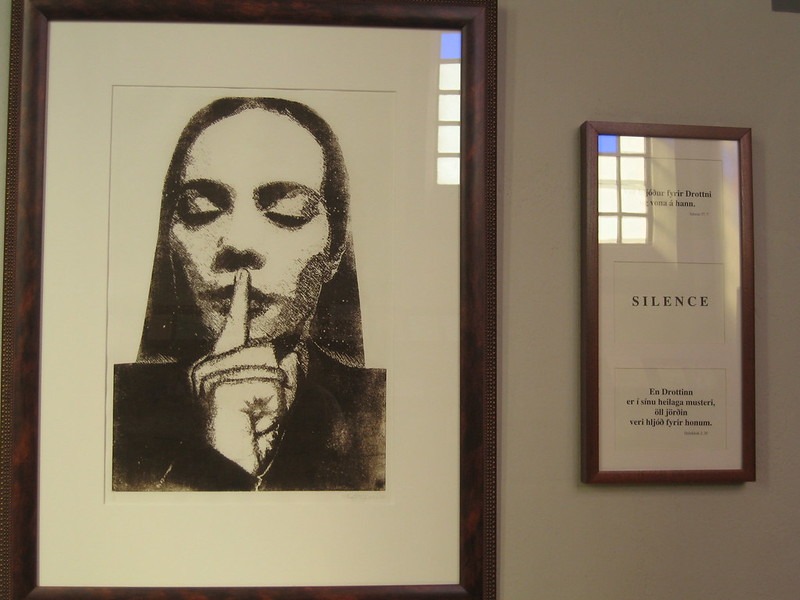

Photo with credit: ‘Silence’, via Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/halighalie/1224462624/in/photolist-2ScG5y-22CPhx1-TKRXkU-qUabzJ-2guVeUh-2atm6Fb-2kfHX2z-8mgDBX-4xuRCa-HpJyY-FhenUq-2aZow5C-2hs32Dx-2jMdXWE-2gnMKdE-7f5XMT-2h4NF7n-2gki8JH-bzaQhn-28gYYdj-HVaGk2-ERSHZ8-8rPuaq-zo3cjA-qzM5Wc-61yiEH-2hp7Zi3-6bQxwM-2a8QSC4-8rPuaf-2b32iQx-8rPv7s-8rPv7A-8rPv7f-8rPv7m-8rPuad-8rPv7h-7jCjyj-VLDqth-8rPuab-ThmnLV-U5FCWG-2jpF96X-bntV8x-H5ZCGw-93719M-dAiqSf-2b3xKfk-pN4qtc-qFPh8

Yajo* lived in place that has produced some of the most brilliant, distinguished academics and professionals. In fact, it once had a flourishing democracy, producing some of the best theorists on state-formation. However, Yajo comes from a place with authoritarian political leaders. Direct and indirect criticism can attract punishment, including life imprisonment. All critical and conscientious citizens have a yearning to speak out, despite the many inherent risks.

This essay explores the precarity of this dilemma. We illustrate the limitations of the globalised system where the sovereignty of nation states comes into tension with utopian ideals about the freedom of human expression. What are the costs of speaking out especially against those who are powerful in society, who hate voices of dissent? What happens to those who raise their voices against instances of injustice? Framed differently, is our society, and the global system failing to stand in solidarity with those who are persecuted for speaking out?

Freedom of speech is widely viewed as a fundamental human right. It enables individuals to express their feelings and thoughts in civic engagement: decision-making through voting, or the right to exercise political opinion through activism and protests. However, some societies take this civic participation more seriously than others. We are told that states must respect the rights, liberties and responsibilities of individuals. Students of international politics and state-formation learn of these ideals and theories. However, beyond academic discourse, to what extent these ideals actually apply in the real world? A critical analysis of these ideals and theories exposes many contradictions. In fact, the opposite is often true: dire consequences exist for those who speak out within oppressive regimes. What does this leave us with? To be silent in the midst of social injustice and political unrest? Or to speak out, even at the prospects of significant personal risk?

Yajo lives in a country where the rulers have considered themselves all-knowing, disregarding voice of dissent. The nation’s citizenry began with a kind request to have their voices heard. This was disregarded. Since then, they have embarked on several forms of collective actions such as hunger strikes or refusing to go to work. The response has been brutality and torture for anyone caught participating in such strikes. It thus became apparent that speaking out and participating in civil activities was infeasible. The word of the authorities was final, and no one dared to speak against them. Other powerful nations have been constrained in responding because of deterrent effect of the principle of state sovereignty.

Yajo emigrated overseas, wrongly assuming that the dictates of their nation’s authorities was only applicable to those within its territorial borders. All the while not knowing that they were all being secretly monitored; the domain of the state extended to those within the diaspora. This extension of the powers of state surveillance can take place through networks of emigrants who are sympathetic to the regime, or through globalised social media services. Yajo resides in a foreign country. Although Yajo had been critical of the state, they did not see themselves as a target, only as a person performing their civic duties. Unfortunately, word went around. As is custom, Yajo travelled home to attend a funeral ceremony, seeing a friend off to the land of ancestors. Yajo had allegedly committed a crime: Yajo had participated in a peaceful march against government inaction on mounting domestic political crises. Yajo was arrested.

Yajo’s arrest illustrates the tensions between holding cherished, democratic ideals and the consequences of actively expressing and insisting on their implementation. In a broader sense, this tension spans across different societies, times and geographies, which limit the ability of people to express themselves or they do so at their own risk. That is, firm convictions and the freedom of expression make some people precarious.

Yajo cannot escape this precarity, as they pay the price of speaking truth to power, losing freedom of movement due to incarceration. Moreover, the cost of speaking out has also been borne by loved ones, as they bear the vicissitudes of separation. Friends have been equally stressed, missing their friend and living everyday not knowing how they are faring or what is going on.

We all know of someone in a similar situation, who has borne great personal consequences in a bid to speak truth to power. We all share hopes and dreams of a good life, and the precarity of navigating between the politics of silence and the consequences of speaking out. But power structures are fundamentally unequal and some people experience precarity, while others do not. Despite the importance given to the ideal of freedom of expression, we seldom reflect on the feasibility and subsequent consequences of speaking out. At times it is an easy thing to do; at other times it is impossible. We are hence caught in between the politics of silence and the yearning to speak out.

*Yajo is a pseudonym.