The refugee campaign in Australia has been one of the most visible and tenacious movements of social activism of the last four of five years. In it, many thousands of people have fought to estabilish a basic principle – that people seeking refuge should not be locked up and treated like criminals. But ever since the introduction of

mandatory detention of asylum seekers in 1992 and, even worse, the “outsourcing” of that detention to Papua New Guinea [PNG] and Nauru in 2001, Australian policy has only become worse.

At the Australian National University (ANU) there has been a vibrant campaign involving students and a handful of staff over several years. We have learned a lot from it and from the broader campaign about activism. I have been involved from the beginning and here is a little of what I think we’ve learned.

Is Activism Worth It?

It is a common complaint that young people just aren’t interested in political activism. When I’m handing out leaflets at ANU, what astounds me most is not when – very occasionally – someone disagrees with what’s on our leaflet. It’s when they won’t even take or look at one. There are many reasons advanced for this apathy: that the “greed is good” message of the 1980s and 1990s created an atmosphere of self-centredness rather than enthusiasm for changing the world; that a more competitive job environment forces students to focus more on getting a good career; that almost all students have to work many hours per week to make ends meet; or that a generation brought up with Facebook, Instagram etc. aren’t inspired by marches and meetings.

I think that there is a more important reason than any of this. The level of disillusionment with traditional politics, parties and politicians is so high that theidea of politics itself has become discredited. Ironically, activist campaigns like ours – although they are actually an antidote to traditional politics – also suffer as a result. Few people actually believe that their own activity can make a difference in the world – so why bother? We usually get a fair reception when campaigning on campus. There is not often open opposition, the response is closer to indifference. So the question could reasonably be asked: why do we continue to fight?

Why we should bother is that with the two major sides of politics putrid on the issue of refugees, our campaign is the only real opposition. Besides, Australian policy and Australian money is still destroying the lives of the asylum seekers themselves. More broadly, how we treat the more vulnerable has a profound impact on the kind of society we are. Once a group is scapegoated for political gain, there is no guarantee that others won’t be added. Pauline Hanson’s 1996 speech said we were in danger of being “swamped by Asians”. By 2016, Asians were forgotten. Now, apparently, we are being “swamped by Muslims”. We do make a difference, even if it’s only in making sure that a generation of kids do not grow up thinking that scapegoating and torturing asylum seekers is acceptable or that there is no alternative to it. We make a difference to our own community.

It is also critical that we demonstrate to the world that millions of Australians do not support these horrendous policies. With far-right groups in Europe, chillingly, calling for an “Australian solution”, we have a special responsibility to denounce the government policy. Finally, between 31 October and 24 November, the men on Manus Island staged one of the most inspiring struggles for their rights – and for human rights in general – seen in recent years. They did so under the most appalling conditions until they were finally brutally evicted. We are not about to give up.

Yes We Are “Preaching To The Converted”

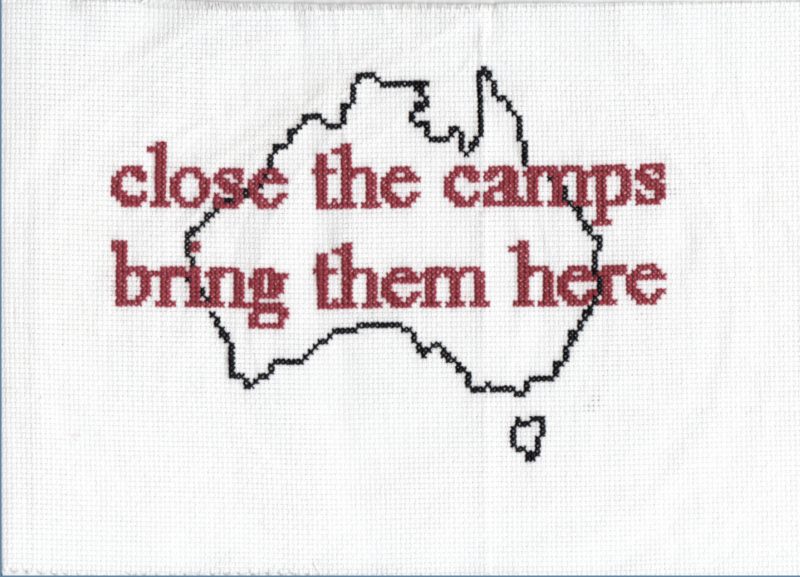

All the polls show that our side of the argument has at least 25-29% support. This is true even when the most difficult question – whether or not respondents supportboat turn-backs – is asked. On questions about bringing the asylum seekers who have languished on Manus Island and Nauru here to Australia, opinion is usually evenly divided, but the “bring them here” response rose significantly during the Manus occupation. In the ACT, public opinion is much better than anywhere else in the country with between 70% and 80% wanting to bring them here. Furthermore, pro-refugee sentiment is higher amongst younger people and amongst those with more education. So a university campus in the ACT should be the very best place to campaign to support refugee rights. Given that, one question is often raised – is there any point to campaigning here at all? Aren’t we just “preaching to the converted”? This is commonly raised in the broader campaign as well. Why hold rallies when the people who come already agree with us? But success in building movements depends, crucially, on the number of activists on the ground. We are not likely to convince people who are very hostile to us at this stage. Nor are we likely to draw people into activity who are in the middle – without particularly strong feelings either way. We want to talk to the people already on our side – the converted – and give them both arguments to make to others and activities that they can carry out. It is these minority communities of activists who always drive the great social changes that make the world a better place. At the ANU this means turning some of the thousands of ANU students who agree with us into activists.

“Secure Your Own Mask Before Helping Others”

We’ve all heard the talk before the plane takes off. “In the unlikely event of a sudden fall in cabin pressure … secure your own mask before helping others”. If we want to help refugees, we’ve got to make sure that the activists here in Australia are looked after as well. For activism to be sustainable it has to allow people to be involved at whatever level they can. There will always be a need for “super-activists” who put in a huge amount of time. But a campaign that only has room for super-activists won’t work. There are too many other things happening in people’s lives. Activism has to be sustainable. So there have to be multiple pathways into it and different ways of doing it. Holding a stall at the pop-up village is important. But it’s not for everyone. Some people have been involved in organising music gigs for refugees, others in social media. The message we’ve tried to put out is that whatever time or talents people have, they’re welcome in the campaign.

“Boredom Is Always Counter-Revolutionary”… And Counter-Activist

The situationist Guy Debord is reputed to have said that “boredom is always counter-revolutionary”. The slogan later appeared on Paris walls during the upheaval of May 1968. Whatever implications it has for revolution, boredom is certainly the enemy of activism. I think there are three reasons why the refugee campaign has tried to come up with new, creative and interesting things to do and ways to protest. The first is obvious – people are more likely to open an interesting-looking package and to respond to activities done with flair. But, just as important is the realisation that what we’re actually selling is not just a message about how refugees should be treated and not treated. We are selling our own activity – because we are trying to get others to do the same – to attract them as activists. So if it looks like we’re doing something boring, we won’t succeed. There is a third reason. This has been a long campaign and many of the tens of thousands of people in Canberra who have come to some activity in it have been to many more than one. It’s not that they are physically tired of coming back to another rally or meeting. But, without victories to show for their efforts, they can feel a sense of futility. “Here we are doing exactly the same thing again and nothing’s changed”. Even small, innovative changes in the protests and in the routine of the campaign can help relieve this feeling. On campus, we’ve done things like bake-sales, little bits of street theatre, and held “Amps Not Camps” gigs. Moreover, a campaign is not like a workplace which is held together by a cash incentive. It is entirely voluntary and those in it need the support of like-minded people, of which social interaction is an important part. Something as simple as drinks in the bar or a party can help to keep a campaign going.

You Can’t Just Say “No”

Outrage at the horrors inflicted on refugees is the main reason why most people have joined our campaign. There are more than enough of these horrors on which to campaign. But we’ve found that to say what we’re against is not enough to convince people. As is often the case the government has created a narrative in which it seems that there is no viable alternative to their policy. The key to this used to be that without tough border controls, millions would come. Now, it dresses up its policy in a fake humanitarianism – that without offshore detention, the refusal to allow anyone who attempts to come by boat ever to set foot in Australia and mandatory detention, there would again be large scale drownings at sea. One simple way of exposing the hypocrisy of this is the lack of even the least concern for those who have been successful “deterred”. There has not been a single word from our leading politicians inquiring about what has happened to these people. Did they die somewhere else? Did they return to squalid camps? Were they forced back to places of persecution and danger?

However, we can’t win the argument with people who are genuinely concerned about drownings at sea without presenting an alternative policy. People often first respond with their heart to the suffering of the refugees we lock up and ban forever. Good! But then our campaign has to present an alternative to be truly convincing. We have to be able to show that there are other ways of taking refugees that avoid the need for them to take dangerous boat journeys. We can be pro-active – processing people’s applications in the transit countries in which they find themselves and then bringing them safely here. Up until 1992, Australia took many refugees but never had mandatory detention. Until 2001, we never had offshore detention in PNG and Nauru. Until 2013, we did not permanently ban those who attempted to come by boat. And the sky did not fall in! Our campaign often emphasises the heart, but our arguments then need to move to the head – showing that we can do things very differently. It is that alternative for which the campaign at the ANU and throughout the country must, and will, continue to fight.