The history of Canberra can be cut many ways. It is, for all intents and purposes, a history of a semi-alpine valley imposed with the burden of Capitol – scoured clean and designed for 25,000 inhabitants, the abstracted ‘smooth faeries’ of Ian Warden’s[1] musings. In reality, we the people grow rogue hairs and hold trauma in our frown lines. The city does the same, with not-entirely-erased road alignments dating back to the 1830s and a palimpsest of planning practices leaving Lego-brick hernias on its northern reaches. Each physical moment inscribed upon this valley, each street and intersection, scarred tree and multi-level apartment block are consequences of and have implications for the notion of Canberra as home.

Across the city’s many building sites there are hanging screens and signs that project a future imagined and promoted, showrooms and turns of phrase, acquired and appropriated artworks. In front of these visions, trucks roll and crack the pavement laid down decades prior for other times and purposes. Shoots of sour thistle, dandelion and petty spurge are quick to colonise the raw aeolian soil. Canberra’s urban stretch marks have emerged from the swell of tension between exploitation and resistance, the weight of trucks and the vegetation flowering in their wake. This is one way to cut the story. It is a story of competing visions of home here in our odd little city. In this way, it is an age-old story about the politics of the structure in which one closes one’s eyes at night.

The theme of this Demos is student activism. Students and young people at large are generally not viewed as actively engaging in or even caring about housing and planning policy in the city. Perhaps this is true. The reason so many students live here in the first place is the choice, made a century ago, to situate Australia’s Capital here. With its assortment of symbolic accruements – of which the Australian National University (ANU) is a well-known one – Canberra draws students from around the world. Many pass through, engaging little in the physical foundations of the city.

However, it is not this simple. Those who look out of the windows of tertiary institutions cannot help but wonder at the beauty and mystery of Black Mountain, and those who are able and desire to can experience the pain of running up Mt Ainslie. Ultimately, these are physical and emotional entanglements with place. Of course, there are also those students and young people who have grown up on Ngunnawal and Ngambri Country and have a bodily attachment to this place. So many who have come to this valley have left their mark, and their actions are deeply embedded in the growth and social policies of the Australian Capital Territory.

CONVENTION.

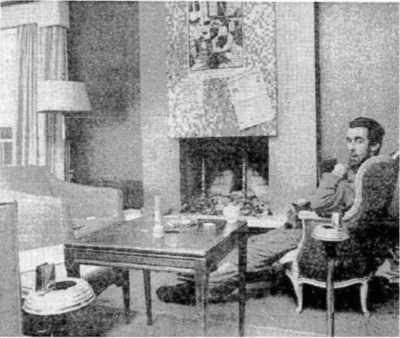

Tim leans forward in his chair in a Civic café and puts the mug of hot chocolate to his lips. Prior to this meeting, we have only seen him in a grainy black and white newspaper photo in which he is reclining on a plush couch inside the squatted Cambodian Embassy. We’re here to talk about the history of the ACT Squatters’ Union that Tim formed with his friends in the early ‘80s. He starts by bursting our earnest bubble: “We just needed a place to live – that’s why we first started squatting. First of all, we squatted everywhere in the inner north. We did up resources so people knew the right things to say to the police so we weren’t hassled for eight weeks. We got a lot of media. It was the time of the Inquiry into Homelessness in Canberra, and we were the face of it.”

The Union had a strong focus on campaigning and broad coalition building. There were influences from youth workers and those involved in the Terrania Creek and Franklin Dam campaigns. Consensus, anti-oppression, local connections and networking, Marxist politics, campaigning via media-friendly actions, a focus on inclusive facilitation formed the basis of the Union. After some time, the Union began to be supported in part by the Builders’ Labourers Federation (BLF) who took it on as a special project. Students were involved from the outset – “We had people who were also students involved of course. I don’t know, they managed to study on the couches of friends. I take my hat off to them”.

“Ah, the Embassy squats”, Tim says of the image that brought us to him. “Well I was sleeping on the couch of a friend and a bloke from the foreign office got drunk in the lounge and was talking about a memo he had read about the Cambodian Embassy on Melbourne Avenue being empty, ballroom and all. The next day me and two mates had moved in!” Over the next eight months, over 200 people were housed in the two-story brick residence, one door down from Parliament House. “The cops couldn’t move us on – we had read the Vienna Convention and visited the United Nations office, and the Embassy was outside their jurisdiction!” he laughs. “It was like negotiations between two sovereign entities. We spoke down to the AFP [Australian Federal Police] from the balcony of the Embassy, and it took them a good eight months to figure out that they could use the Convention to their benefit too.”

We ask Tim what he felt the Union achieved. He shrugs, “Well, we housed people who needed it”. He gestures around us, up to the metal and glass monoliths of Bunda Street. “These eight hundred thousand dollar apartments here in the city? Well, that’s because of us! They weren’t thinking of having housing here in the city before we were here.” We laugh, but he suddenly turns serious, “Well, they’ve been built, and they’re in a great spot, and when the revolution comes… Well, they’ll make a good place for folk to live”. We are left wondering about the possibility of that hope.

UNION.

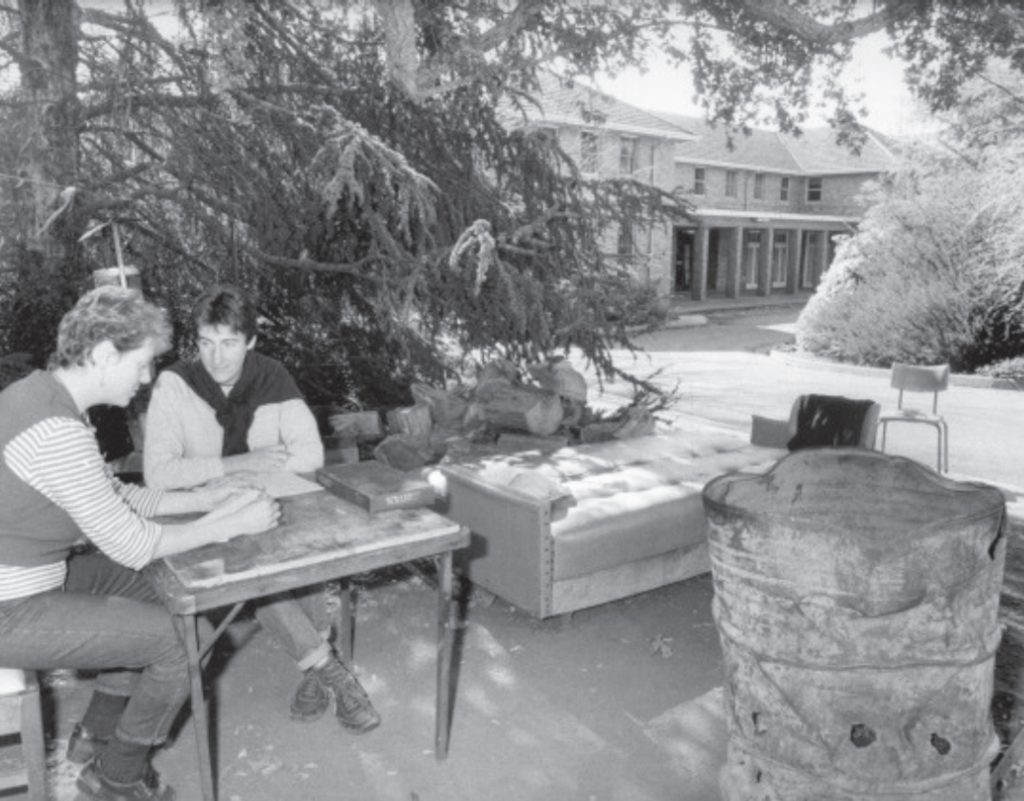

It was a cold winter in ‘83, when the fight for Havelock House commenced. The canvas tents were pitched under the pines on Northbourne, and the bitter winter cold taunted the picket line. At the height of a Canberra housing crisis, one of the city’s larger public servant hostels had just been handed over to the Federal Police and was in the process of being converted into their Headquarters. It was time for action.

We’re on the phone – I am seated on a doorstep in the inner north and Peter is in his garden in Oaks Estate, out Queanbeyan way, with a beautiful veggie patch scratched from the hard-packed earth banks of the Molonglo. Peter is a lifelong unionist and he has lived through one of the most volatile parts of Australia’s union history. He gently reminisces, “The Havelock blockade got started by a bunch of young locals supported by the Social Work Union. I was secretary of the Builders’ Labourers Federation and we were working on the new Parliament House at the time. There were a lot of housing access issues in Canberra because of that. That’s the genesis of the picket line.”

Canberra’s young folk stood front and centre – youth workers, employment placement workers and union activists. It was the Canberra Youth Refuge who wrote to the Canberra Times. There were protests during Bob Hawke’s visit and his support was sought to stop the closure. By the end of the months-long picket, Havelock House and its future had been discussed in Federal Parliament and a meeting attended by no less than six Ministers was convened by the Unions. Peter puts it into context: “It was a time of the black bans. We called a ban on one of the old houses on Northbourne that was going to be knocked down and turned into flats probably. We also had a four-monthlong picket of the National Library of Australia and two schools, demanding asbestos be removed from the sites. At the time, the unions had a strong focus on broader social issues.”

“So we at the BLF supported the picket of Havelock in no uncertain terms. I think there’s still a telegram hanging up there in Havelock House from me to the camp, Stand firm, and you shall prevail. I went down to the frontline many times.”

The picket line did indeed hold strong, and a split-off group called ‘Havelock House for the Homeless’ voted to squat the building. Plywood intervened and many were arrested. In the end however, the AFP and the Government gave in to growing pressure. The Inquiry into Homelessness in Canberra commenced soon after and the building was handed over to the newly formed Havelock Housing Association for social housing in 1988. Peter was blacklisted from working in the late 1980s as part of the Federal Government witch hunt against union organisers. One of his jobs following this period was as a handyman for the Havelock Housing Association.

He sighs and brings us back to the present.

“Well, Havelock is still there because of the collaboration and support between the unions and the community groups. It’s really awful what’s happening now though, with the ACT Government in bed with the developers. They’re shutting down all the social housing places and pushing everyone out into the margins, like they’re meant to be there. It’s appalling.” I look out to the Bruce Ridge bush and think of how much we owe this gentle voice on the other end of the line.

MIDNIGHT.

In 2010, nearly thirty years after the last tent decamped, the Canberra Student Housing Co-operative was formed. It now occupies one wing of Havelock House. ‘The Co-op’, as it is affectionately known, was formed by a group of students seeking more control of their housing situation, a more affordable rental option in a saturated market and a tighter knit community than what typical student housing offered.

One of the founders, Leah, shared these goals when we asked her about the experience of organising in the early days. “We definitely saw it as activism. We would have loved to buy a place but didn’t have any cash or institutional support and it was really just a lucky break with getting in at the right time at Havelock. Starting there gave the Co-op idea some legitimacy, and then once students could actually see it and the fun, inclusive culture it was developing, they could actually get behind it.”

It may have been a lucky break with the Havelock Housing Association, but the student connection to the building goes way back. I meet Emma, a current resident in the Co-op, in the bright sun outside Smith’s Alternative in the city. The wind whips in the gulf between the post office and the Melbourne Building, one of the earliest built in the city. Our backs are to the 1920s colonnades.

“I’ve lived in ten different places in the last five years. Apart from my childhood house, the Co-op is the closest I’ve gotten to feeling ‘at home’. For me, this space is perpetually in motion. Not that it isn’t peaceful; it’s one of very few places I have been where silence does not cause anxiety… I sit quietly on the back step, watching the Moore St currawongs. Sam G leaves them some mealworms. Workers cruise past on the way home from work; picking up their kids. Bit of pink sky above the fancy blocks across the road—$500/week for a single bed apartment.”

Recently, the allocation of social housing to Havelock House has come under pressure again – this time, from inner-city gentrification and the growing demand for the high value land. Other social housing complexes in the area are being demolished and their residents are being moved to the far north of the Territory. Walking past the boarded-up Northbourne Flats in early Spring, Diane, one of the few remaining residents of the social housing block just up from Havelock, hurtles out of her unit. She looks harried but hopeful and, with only a brief introduction (‘Oh! You look like my son!’), goes on to talk of plans being made by a group of residents to secure funding to retain a block of the flats and build a community centre there. People are pushing back again: “Unit 16 faces Northbourne. Those kids wake up to light rail construction and an enormous wall of orange: Geocon’s Midnight Building getting a facelift. Molonglo Group is an ongoing dinner joke and an ongoing threat. Should we buy a two-year internet subscription? What if we’re not here in two years?”

The axe may have passed over Havelock for now, but the threat has shifted conversations onto why the Co-op is a community worth maintaining. Collaborations with the ANU have been a focus in recent years, with the Co-op seeking support from the University to purchase or refurbish a building on campus. They’ve campaigned in numerous ways, forming a student political party, approaching the University Council and even hosting the Vice Chancellor for dinner. Unfortunately, most of this has been to little avail. It seems more and more likely that the future of the Co-op will be secured in partnership with the broader housing sector, a sector which past students and young people have played an active role in establishing.

PRESENT/FUTURE.

Stories drip into tiny rivulets and broader streams which carve the channels of the city’s history. All of us here in Canberra are looking for places to build community and attachment, not just to sleep. We seek to comprehend the small, semi-alpine valley we have come to live in and to assert some control over its future. The story of housing policy in our city is really a story of collaboration between disparate groups and communities – students, informal action groups, unions, formal housing associations – that have taken action against the harsh, isolating reality of developer-driven construction. Canberra is once again in the throes of ‘urban renewal’ and expansion; demolition dust is already in the air. Resistance against the harsh settling of this dust has once again begun.

Steve is curious about Canberra’s history and how it bleeds into the present. He has Masters in Archaeology and Community Development. Steve took the two images in this piece along Northbourne Avenue.

Emma is a former Demos editor and has just graduated from ANU with a BA.

Both Emma and Steve are former residents of the Canberra Student Housing Co-op.

Catherine Claessens in an emerging artist and aspiring activist and teacher from Canberra. She works mainly in printmaking, drawing, and watercolour to explore issues of social justice, religion and sometimes simply the strange and beautiful environment around her. Catherine graduated from ANU School of Art & Design in 2016.