Within Hannah Arendt’s classic New Yorker essay, ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’ (1963) and subsequent book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), an alternative explanation for the origins of the human capacity for evil are explored. Her famous ‘banality of evil’ thesis is based on her first-hand witnessing of the Adolf Eichmann trial in 1961. Eichmann, a Nazi who was responsible for the deportation and deaths of millions of Jews in occupied Europe, would be found guilty of his crimes and hung in Israel in 1962.

In reading Arendt’s New Yorker essay, which consists of Arendt’s coverage of the trial as it unfolds and her reflections on it, I was struck by a passage towards the beginning of her essay. Arendt asks questions shared by a traumatised generation of Jews, gentiles and Germans wandering through the unsettled dust of a second catastrophic war, as it hung in the air and left all affected asking, ‘how…why?’ Arendt believes Eichmann should be on trial for ‘his deeds, not the sufferings of the Jews’. Her questions—shared by a generation of Europeans, and loudly denounced by many fellow Jews, are poignant, honest, and allude to something else—something hidden in the dust. According to Arendt:

Justice demands that the accused be prosecuted, defended, and judged, and that all other questions, though they may seem to be of greater import—of “How could it happen?” and “Why did it happen?,” of “Why the Jews?” and “Why the Germans?,” of “What was the role of other nations?” and “What was the extent to which the Allies shared the responsibility?,” of “How could the Jews, through their own leaders, cooperate in their own destruction?” and “Why did they go to their death like lambs to the slaughter?”—be left in abeyance.

For me, a sense of collective responsibility is seared onto the page here, as it leaves everyone—Jews, Germans and liberators—vulnerable to scrutiny and guilt. But was this guilt felt? In Arendt’s report from Germany in 1950—11 years before witnessing the Eichmann trial— her answer was no. Rather:

…the indifference with which they [Germans] walk through the rubble has its exact counterpart in the absence of mourning for the dead, or in the apathy with which they react, or, rather, fail to react, to the fate of the refugees in their midst (Arendt, 1950: 249).

Arendt’s observations in the immediate aftermath of war led her to believe that Germans sought not only to ‘escape from reality’, but also to ‘escape from responsibility’ for the causes of war (Arendt, 1950: 250). It would seem that rather than openly addressing a nationally-felt trauma with compassion and collective reconciliation, Germans remained apathetic towards the suffering of those most affected by war, refugees, in addition to that of their own people.

A political philosopher taught by Martin Heidegger in 1920s Germany, Arendt’s greatest academic work was done in the post-war era, where she sought to understand our moral judgements in a time of immense political upheaval. Europe in the 20th century was undoubtedly shaped by two world wars, and the rise and fall of Fascism and Communism. In 2016, the political situation within Europe and throughout the world is comparatively more stable and safe. However, perhaps as a product of the human condition (a title of one of Arendt’s books), there remains a strong human tendency to protest and challenge the status quo. Today, we remain restless as we redress inequalities and promote kind, compassionate, human rights-based virtues. Did we finally discover our moral compass from the rubble of the 20th century, whilst feeling a sense of responsibility to protest against evil, whether sinister, insidious or banal?

The immense destruction and human suffering of World War Two prompted social scientists of all varieties to attempt to make sense of what had just happened. The 1960s and 1970s was also a period dominated by the Vietnam War, and social activism as we know it today was born out of an anti-war movement where immense groups of people could protest against their government and successfully change its foreign policy. Whilst the act of protesting was by no means a new concept, there was perhaps a new interest in understanding what motivated groups of people to band together and publically demonstrate dissatisfaction.

The idea of a collective responsibility to protest has its detractors who argue that there is no such thing as group morality. According to this argument, people possess and exercise individual moral agency, and ‘participants in this controversy have asked, can we distribute collective responsibility across individual members of a group?’ (Smiley, 2005). Their answer is no, as it would require group self-consciousness—which does not exist, as we are all physically incapable of thinking and feeling another person’s exact thoughts and feelings. At most, people can only hold shared attitudes, which could direct a group of individuals to protest, and allow the possibility for collective responsibility among group members. According to Max Weber (1914: 13), a founding sociologist who remains revered today, ‘individual persons […] can be treated as agents in a course of subjectively understandable action’. Weber (1914: 13) would reject the notion that a group of people can possess collective responsibility, as ‘we cannot isolate genuinely collective actions, as distinct from identical actions of many persons, and because groups, unlike the individuals who belong to them, cannot think as groups or formulate intentions of the kind normally thought to be necessary to actions’.

These discussions about the collective responsibility to protest have thus far referred to living people. But there are many examples where past actions (or inactions) of the former living, have been held accountable for present injustices. Past instances of imperialism, slavery, institutionalised racism, sexism and war has fuelled strong arguments for reparations, increased civil liberties and national apologies. Criticisms arise from members of a society, and state actors who may not feel responsible for the actions of past generations of people, or former governments. This criticism has allowed for conditions where the perpetuation of an injustice or resentment felt by people can continue. National reconciliation efforts in South Africa, Australia and Germany have helped address societal injustices or resentment by accepting responsibility for the actions of past governments. However, it is perhaps harder to influence the beliefs of individual citizens who may not have directly caused the suffering of others, especially if the injustice took place in the distant past.

To counter this problem, Thompson (2002, 2006) and many others have suggested that collective responsibility can be assigned to people if they benefit from the prolongation of an injustice. Clearly, the average Belgian citizen did not directly cause the deplorable subjugation and suffering of Congolese people during the colonial rule of Belgium between 1876 and 1960. However, there is reason to believe that the current wealth and prosperity of the Belgian government and citizen can be partly attributed to exploitive economic policies that has kept Congo poor, and Belgium comparatively rich. Similarly, whilst no living Australian played a role in Australia’s Frontier Wars, or the gross mistreatment by early settlers of indigenous inhabitants, non-indigenous Australians are inherently privileged, and continue to benefit from the consequences of an unjust and exploitive colonial history. Perhaps, according to this line of thought, we are collectively responsible for conditions which allow for the continuation of societal and cultural damage wrought upon Indigenous Australians today.

So where does this discussion leave us? Is the human capacity for evil sinister, insidious, or banal as Arendt has argued, and do we have a collective responsibility to redress injustices? We only need to look at the recent past to notice instances of deliberate, prolonged and routine acts of evil. Apathy is a feature of the human condition, regardless of age or political orientation, although it is by no means a new phenomenon, given that Arendt refers to an apathetic German nation in the aftermath of Nazi rule. German apathy remained constant throughout the dangerous rise of Nazism, the Nazi trouncing of Europe, and the rubble it left in its defeat. Arendt should know, having witnessed and documented how apathy could replace collective responsibility in a time when sociocultural resonance was most needed in German society.

Is apathy evil? ‘Evil’ is a strong word—one which I am hesitant to use, especially as it tends to conjure up the very worst in human nature. Apathy is not evil in itself, but it might be conducive for it to exist, as it allows for evil to go unrecognised, unchecked and almost unstoppable. Apathy is the prelude for some of the worst acts of human behaviour in the 20th century, and we remain capable of sliding back into its silent embrace. The German people existed within this apathetic embrace, as Nazis began rising to power from the early 1920’s. Within 20 years the embrace became a chokehold. Adolf Eichmann evolved from apathy, his evilness developed into the banal form Arendt so keenly observed at his trial. The banality of his evil was perhaps the extreme endgame of his apathy as it took root as a young German before the war. Had there been a greater societal sense of collective responsibility to protest against pre-war Nazi injustices, Eichmann may never have had the freedom to commit crimes against humanity.

At the end of her life, Arendt pondered on what she had learnt from her now famous correspondence of the Eichmann trial. Arendt (1971: 418) asks;

Is our ability to judge, to tell right from wrong, beautiful from ugly, dependent upon our faculty of thought? Do the inability to think and a disastrous failure of what we commonly call conscience coincide?

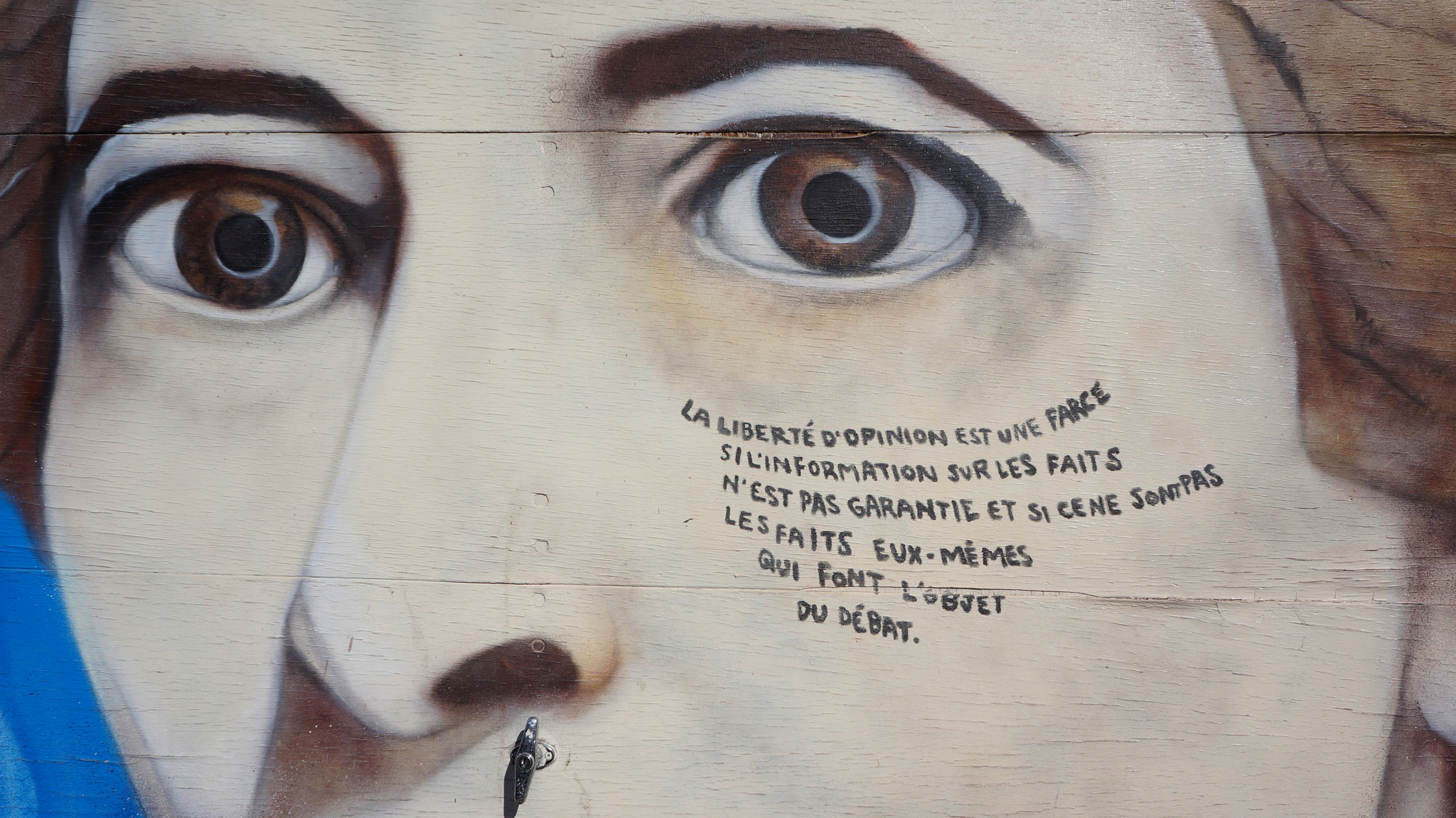

Her answer is yes; that we must ‘demand’ critical thought be exercised in all people regardless of their intelligence or social status. Perhaps thought, even at a shallow depth, is enough to sweep away apathy and bridge the divide between ‘us’ and ‘other’. This, I argue, is our collective responsibility and best chance to redress injustice, or else;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, /

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity. (Yeats 1-8)