Banner image: ‘Posterboys’, Bridget McKenzie, via Flickr.

Masculinity is in crisis. This is a readily agreed upon view amongst many scholars, pop psychologists and media figures alike.

Examining declining educational achievement, high suicide rates, and a growing cohort of ‘angry men’ determined to reclaim a lost sense of masculinity, it is clear, according to some, that something is going wrong with men across the world. Pankaj Mishra (2018) argues, for example, that thinkers and leaders around the world –from Jordan Peterson to Donald Trump – are desperately try to reclaim a traditional notion masculinity in the wake of an ‘emasculation’ that has occurred through social changes in recent decades. He argues:

It is as though the fantasy of male strength measures itself most gratifyingly against the fantasy of female weakness. Equating women with impotence and seized by panic about becoming cucks, these rancorously angry men are symptoms of an endemic and seemingly unresolvable crisis of masculinity (Mishra 2018).

But what do we actually mean when we’re talking about a crisis in masculinity? While the notion of a masculinity in crisis is increasingly assumed in both academic and public debate, its growth in popularity has resulted in the concept being difficult to define, and in turn it being used by people for a range of different ends.

By interrogating the two dominant approaches to a ‘masculinity in crisis’ I argue that we can see a range of the problems associated with the idea. Firstly, the notion of masculinity in crisis totalises the role that masculine norms play in men’s lives so much that nothing else ends up mattering. Men become defined by masculinity, and nothing else. Whether from sociology, academics or thinkers like Jordan Peterson, an incessant focus on masculinity ignores much of the complexity of men’s lives, and reduces all solutions to the problems men face to changing gendered norms. I argue for a broader approach to understanding men’s lives, one which sees many of the issues facing modern men as sitting within a broader context of social breakdown and decay in a neoliberal era.

My question about the actual features of the crisis of masculinity arises in the context of the growth of an online sphere described as the ‘manosphere’ (Marwick and Caplan 2018). The manosphere is extremely useful in examining the notion of a masculinity in crisis as it provides a clear representation of the different ways the concept is invoked in public debate. On one side, participants in the manosphere frequently discuss feeling as though they exist within this crisis of masculinity, and in doing so turn to the manosphere as a way to deal with this. Manosphere participants frequently valorise traditional masculinity, arguing that a return to historical norms and privileges is the solution to the problems they are facing. On the other side of the ledger, the manosphere is increasingly being studied as a toxic symptom of the crisis in masculinity, and in particular as case study of the “backlash” (Faludi 1991; Hodapp, 2019) against challenges to masculine norms. The solution for opponents and critics of the manosphere is to further break down masculine ideas so that the return to a historical version of masculinity is not possible. The manosphere therefore captures the different what different constituencies think about a masculinity in crisis, in turn highlighting the contradictions in the uses to which the term is put.

So, what is the manosphere? According to the popular website Know Your Meme (2015) the manosphere is: a neologism used to describe a loose network of blogs, forums and online communities on the English-speaking web that are devoted to a wide range of mens’ interests, from life philosophies and gender relations to self-improvement tips and strategies for success in life, relationships and sex.

While this definition focuses on the English-speaking web the manosphere has increasingly spread to non-English parts of the world as well. The manosphere operates across a range of online forums and spaces. This includes social media and sites such as 4Chan, 8Chan, Reddit and Youtube, websites, and community and news forums such as incel.me (and incel forum) and trp.red (a forum for participants who align to the philosophy of The Red Pill).

The manosphere fits within a broader a men’s rights movement, which is re-emerging in online spaces (Hodapp 2019). The men’s rights movement is a reaction against feminism, part of a broader backlash against feminist movements and ideas. As Lyons (2017, p. 8) explains, the manosphere: includes various overlapping circles, such as Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), who argue that the legal system and media unfairly discriminate against men; Pickup Artists (PUAs), who help men learn how to manipulate women into having sex with them; Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOWs), who protest women’s supposed dominance by avoiding relationships with them; and others.

Manosphere participants frequently engage in discussions around masculinity and in particular articulate the idea that masculinity is under attack. As Ging (2017) describes, much of the discourse within the manosphere is based in evolutionary psychology and genetic determinism, one that relies heavily on essentialised biological understandings of men and women. These notions valorise a notion of what Ging and others (e.g. Massanari 2017; Salter 2018) describe as geek culture, with men seen as rational and logical, while women are irrational, emotional, and most of all hardwired to pair with what they describe as ‘alpha males’ (Ging 2017). Men, and in particular many of the inherent traits, of masculinity are seen as under attack from feminism, resulting in a range of negative impacts.

Members of the manosphere have been engaged in campaigns of abuse and misogyny both on and offline. This has included #gamergate, a systematic campaign of abuse targeted at female games developers (Massanari 2017; Salter 2018), and #TheFappening, which consisted of the illegal release and sharing of thousands of nude photos of female celebrities (Massanari 2017; Moloney and Love 2018). At an even more extreme level, antifeminist and misogynist sentiment has been connected to a number of mass shootings, massacres and terrorist events (Dragiewicz and Mann 2016; Kalish and Kimmel 2010). This includes high profile shootings and terrorist attacks by incels. Incels believe that due to a mixture of their own genetic problems, as well as women’s inherent desire to mate with attractive men they call ‘chads’ that they are unable to find women who want to have sex or form relationships with them. Incel forums often include angry rants against women for their unwillingness to enter into relationships with them. In 2014 the self-described incel Elliot Rodgers killed 6 people in a shooting in Isla Vista in the United States, and in 2018 Alek Minassian killed 11 in a van attack in Toronto. Both cited anger at their status as incels as motivations behind their attacks.

How do we conceptualise a masculinity in crisis when it comes to the manosphere? I argue that there are two broad ideas. The first comes from within the manosphere itself, with participants within the space seeing their participation as a way to deal with a crisis externally imposed upon them. The second conceptualisation comes from those who view the manosphere from the outside, arguing that the space is a symptom of broader issues with masculinity as a whole, which is creating a range of crises. I described these explanations as (1) a loss of male purpose, and (2) aggrieved entitlement.

Explanation One: A Loss Of Male Purpose

Manosphere participants create a simple narrative to explain their sense of a masculinity in crisis. This explanation goes something like this: There are inherent and genetically determined differences between men and women. In previous decades – i.e. the 1950s and 1960s – these inherent differences were respected and society was much more harmonious. Society, however, has always been gynocentric – i.e. focused on the needs of women. Women are revered and looked after by society, while men engage in the hard and dangerous work of building society. Recent social changes, in particular the rise of feminism, have not only reinforced this notion of gynocentrism but have taken away any purpose or value men have in our society. They have removed the balance of our social gender roles, leaving women in a dominant position. In turn, women have begun to demand to take over men’s role in society, while at the same time attacking men’s inherent maleness. This has left men out at sea and rudderless.

Much of the discourse within these communities points to a range of issues to argue in particular against any notion of ‘male privilege’, including a focus on rates of domestic abuse perpetrated against men, male suicides and workplace deaths and male educational attainment. These issues, they argue, show the ridiculousness of the demands of modern feminism, showing that it is women who in fact are privileged in our society. This is frequently followed by misogynistic attacks against women, particularly online. Many of these campaigns of networked harassment (Marwick and Caplan 2018) are viewed through the lens of divine justice. Harassment provides an essential purpose for men who have lost a sense of purpose in their lives, with men arguing that they are taking back what has wrongfully been taken from them (Copland forthcoming).

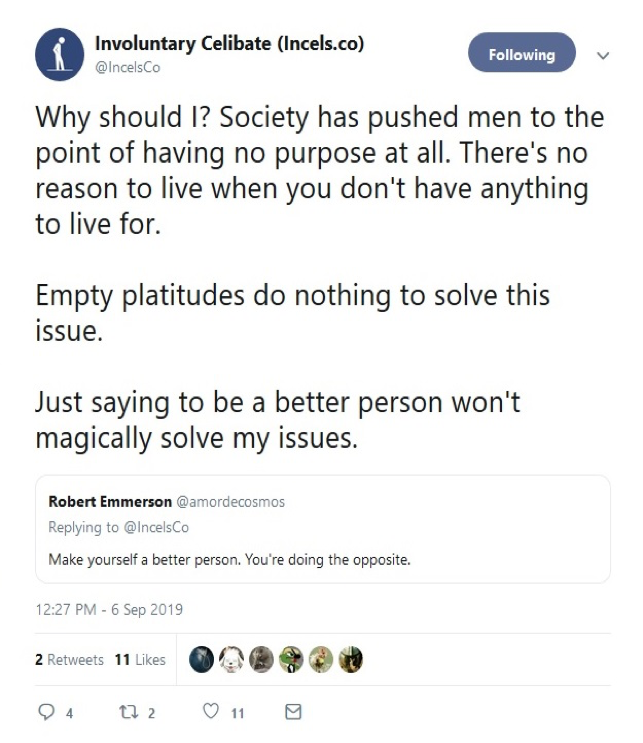

Here are some examples of this approach. Figure one for example shows a tweet from one of the most prominent incel accounts on Twitter, @IncelsCo. This incel responds to a common argument directed at the community – that they could obtain a partner if they made themselves better people. @IncelsCo argues against this, stating that society has removed all purpose for men, meaning that self-betterment is a useless strategy.

Figure 1: Tweet from IncelsCo

Figure Two is an example of the type of meme posted from the subreddit on Reddit r/MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way). Members of MGTOW believe that relationships with women are so detrimental to men, that men must remove themselves from relationships entirely. They should ‘go their own way’. In this meme we can see a defense against the so-called attacks men have faced from feminism in particular in recent decades, with the final line that “you did absolutely nothing wrong for being a male and you have absolutely nothing to apologize for.”

Figure 2: MGTOW meme

These examples encapsulate the ‘loss of male purpose’ approach to a masculinity in crisis. Proponents of this approach argue that men have come under attack, and that these attacks have resulted in a range of negative social outcomes from men. The behavior of men in the manosphere – including online harassment – is simply a response to these attacks. The solution in turn lies in feminists and social justice activists renouncing their demands, and allowing men to express their masculinity in normal and natural ways.

Explanation Two: Aggrieved Entitlement

The second explanation for the crisis of masculinity is linked to the first, but in doing comes to very different conclusions. This approach is explained in multiple different ways, but for the purpose of this article I am going to use Michael Kimmel’s notion of ‘aggrieved entitlement’.

In his book Angry White Men, Kimmel (2017) argues that there is a growing cohort of, specifically, white men, who are angry about their lot in society, and are taking out this anger through their votes and political actions. Kimmel argues that these men are witnessing a loss of their own power and privileged role in society, primarily at the hands of social justice movements and feminism. These men, he argues, are socialised to feel entitled to this power and privilege, and, are becoming aggrieved at it being taken away. As he argues:

The new American anger is more than defensive; it is reactionary. It seeks to restore, to retrieve, to reclaim something that is perceived to have been lost. Angry White Men look to the past for their imagined and desired future. They believe that the system is stacked against them. There is the anger of the entitled: we are entitled to those jobs, those positions of unchallenged dominance. And when we are told we are not going to get them, we get angry. (Kimmel 2017: 21)

This anger is one that looks back to a better world (for men), seeing a huge loss in the male position. This anger has been best epitomised by the emergence of a new cohort of right wing figures who focus on men and masculinity. The psychologist Jordan Peterson, for example, built a career based on an analysis of a masculinity in crisis. Peterson lays the blame for many of the problems of facing men on a vast array of progressive social changes over recent decades. He then provides an array of self-help activities people can undertake the make themselves better to deal with these issues. His book Twelve Rules for Life (2018) includes tips such as stand up straight, make friends with people who want the best for you, and treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping. While these tips are often common sense, they are then mixed with an array of anti-feminist and broadly anti-left sentiments.

Already we can see the similarities between an analysis of aggrieved entitlement and the ‘loss of male purpose’ approach. Both agree that there have been major shifts in society, and that these have had impacts on the position of men. They differ however in their analysis of the value of masculinity, both as a historical condition, as well as a response to the current crisis.

Proponents of the ‘aggrieved entitlement’ thesis in particular argue that there are inherent issues with the type of masculinity championed by members of the manosphere, which is often described ‘toxic masculinity’. Toxic masculinity describes the ‘the constellation of socially regressive male traits that serve to foster domination, the devaluation of women, homophobia, and wanton violence’ (Kupers 2005, p. 714). This approach argues that violent and authoritarian acts from men occur due to a strict adherence to masculine social norms. Social expectations that men should be dominant and violent, while also limiting their emotions, results in expressions of violence. Masculinity in itself is not toxic, but has toxic elements, ones which some argue men are increasingly turning to in response to the rise of feminism and other social progress. Toxic masculinity, a form of masculinity in crisis in its own right, is now being blamed for male violence and the domestic abuse epidemic, as well as the election of Donald Trump, the Brexit vote, and even climate change (Salter 2019).

We can in turn see two clear understandings of a crisis in masculinity — one which is imposed upon men from the outside, and a second which men create on their own through engaging with the more toxic traits of masculinity as a response to social changes. Members of the manosphere see a crisis that has been inflicted upon them by a world that is anti-men. Critics of the manosphere see the crisis instead as being internally driven, primarily as a failure of men to give up their privilege and accept recent social changes.

In turn these two visions of masculinity come to vastly different conclusions. For members of the manosphere their anger is entirely justified and represents a fair reaction against attacks from modern society, in particular progressive changes in recent years. They see a genuine loss of purpose and react in kind. An aggrieved entitlement approach however does not see the crisis of masculinity through the lens of purpose, but instead sees male anger through the lens of power. Men are only angry because they are losing their power and privilege, particularly in their relationships with women. This, at least implicitly, diminishes the anger these men are feeling. Anger based in a loss of power is not justified, and in turn those who are feeling it are frequently mocked and attacked.

I argue that these approaches fail in two ways. Firstly, both responses, in different ways, essentialise masculinity and male power. Secondly, I argue that these approaches totalise the male experience, framing men’s lives as occurring entirely within the lens of masculinity. Literature around masculinity and in particular the crisis in masculinity only examine these issues through the lens of masculinity, missing out much of complexity of the male experience, and in particular the range of social circumstances that contribute to the crises men are often facing.

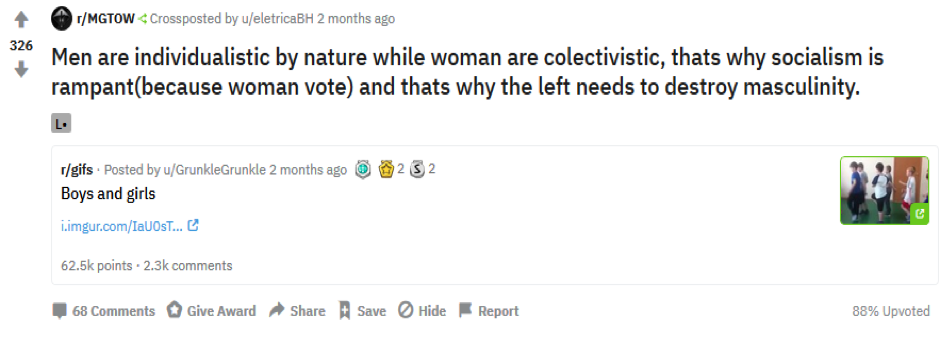

Notions of the loss of ‘proper manhood’ that exists within manosphere discourse essentialise masculinity and femininity as rigid behavioural traits. These essentialised traits often favour men, who are seen as rational and individual, while women are irrational, overly emotional, and genetically reliant on men (Ging 2017). We can see this in a post from a user on the subreddit r/MGTOW (Figure 3), where the user argues that ‘men are individualistic by nature while woman [sic] are collectivistic, that’s why socialism is rampant(because woman [sic] vote) and thats [sic] why the left needs to destroy masculinity’. This was matched with this video of school children practicing marching, with the boys marching in a chaotic manner, while the girls are in lockstep with each other. The video, according to this user, indicates that men are more individual by nature, while women are more likely to follow orders. Here we see a mixture of essentialised understandings of gendered behaviour, alongside a rather unique political critique. This narrative argues that the goal of social progress is to destroy masculinity, and in turn that it is up to men to defend against this.

Figure 3: MGTOW Reddit post

It is in this post that we can see where some of the ‘loss of manhood’ arguments collapse. Most obviously this approach does not analyse how our society socialises boys and girls, treating gendered traits as inherent and genetic. Moreover, it engages in a reactionary politics, which in many ways reinforces many of the complaints men in the manosphere make. In particular, the claims men in the manosphere make about the inherent nature of gendered traits contradict directly the complaints they make about society. As already noted, a dominant theme within the manosphere is that masculinity and femininity are inherent traits – traits that are being increasingly overlooked in modern society. At the same time, however, there are also frequent complaints about the roles men play in society, in particular their alienation from children as fathers, society’s overdependence on them for dangerous work, and the assumption that men are inherently violent and abusive. There is a clear contradiction here. If masculinity and femininity are inherent then so are the roles that men and women play in society. There is no escape.

This however does not make the analysis of ‘aggrieved entitlement’ a good conceptualisation of ‘a masculinity in crisis’. Aggrieved entitlement as an analysis also essentialises a form of manhood, in particular the drive for men to dominate women. While much of this discourse explains that the desire for male domination comes from social upbringings, it does little to actually theorise the social situations that drive these conditionings, instead, adopting a form of analysis that, at least implicitly, sees the drive for male domination as being inherent or essential. Van Valkenburg (2019) for example argues that current academic discourse around the online manosphere assumes that men who participate in the space are inherently misogynists. They are misogynists first, with the manosphere being a space they enter to express their misogyny. As he argues therefore current narratives associated with the manosphere ‘simplistically pathologises manosphere discourse while leaving its misogyny undertheorized.’ (Van Valkenburg, 2019:1) Similarly, studying ‘pick up artists’ in the UK, O’Neill (2018) says that current approaches paint participants as ‘pathetic, pathological, or perverse’, with the misogyny of pick up artists being treated as inherent or essential. An aggrieved entitlement approach can easily fall into the trap of simply arguing that members of the manosphere are ‘bad’. This again creates a situation where there is no escape. If men are simply bad – or pathetic, pathological, or perverse – then there simply is no way to fix the problems associated with their behaviour.

Brought together I argue that these analyses of a masculinity in crisis totalise the male experience, seeing all responses to male crisis through the lens of masculinity and masculinity alone. The crises these men face are therefore due only to either the loss of masculinity, according to one theory, or their constant desire to reinforce masculinity, according to another.

The clearest way we can see this is through the way in which masculinity is assumed to be white and European. It is notable, for example, that Michael Kimmel’s book is titled ‘Angry White Men’. While of course it is reasonable to focus on this cohort of men in his study, the analysis that follows often eventually assumes that all men experience and express masculinity in this way. Experiences of masculinity are treated as the same across cultures, races and sexualities. This results in a particularly messy approach toward thinking about ‘male privilege’, one which places the power men experience as men above all other social experiences.

For example, male power and privilege are, in public debates in particular, increasingly the focus of the causes of domestic violence (Salter 2016). However, this assumes that men have equal access to privilege across our society, and that this privilege operates in the same way for different social groups. How, though, can we effectively use privilege to explain the high rates of domestic violence experienced within Australian Indigenous communities (for details see Thorpe 2018)? Many Australian Indigenous communities come from backgrounds of deep collective trauma due to the impacts of colonisation. Indigenous people are more likely to have faced imprisonment across their lifetime, or struggle with addictions to alcohol and other drugs. While gender is clearly part of the puzzle when examining domestic violence in these communities, it is, and cannot be the only factor. To explain these circumstances through the lens of privilege and power simply totalises a notion of masculinity, and ignores many of the histories and life circumstances facing different men.

Moreover, this totalising approach to masculinity ends up ignoring what men who are expressing this anger are actually saying. In particular, both of these approaches assume particular masculine expression within these communities, ignoring the moments of intense emotionality (Rafail and Freitas 2019), as well as cooperation and collectivity. Some men certainly valorise masculine ideals, but many others don’t. Those who do, do so in far more complex ways than even they realise, frequently acting in ways that contradict the very notion of masculinity that they valorise.

Any totalising theory of masculinity either misses these moments (particularly in the loss of male purpose explanation), or attempts to ascribe them as strategies used to continue domination, fitting elements that contradict key theories awkwardly within them (particularly in the aggrieved entitlement explanation). Men, in this picture, are almost inherently driven to strive toward the domination of masculine norms, with all practices that occur within male spaces being part of a strategy to facilitate this end.

One example of this is the prominence of suicide notes that appears in particular in incel communities. This is one thing that really shocked me in my research when I first started, but unfortunately at the same time is something I eventually became used to as I saw them appear more and more. Here is an example of such a note, which appeared on the incel form r/Braincels on Reddit:

Today, 14/07/2018 is the day I will end my life. Since I was a kid I was fed up with “Don’t worry it will get better”, “You will find someone” and “Tomorrow is a new day”. Enough with this bullshit.

it’s not even that I want a SO (significant other) anymore. Women are awful. People are awful. I have no friends. My family is very distant, they couldn’t care less if I roped. The only reason I was alive these few months are you guys. You were the ones that showed me how the world really is, and you always stood by me.

I’m scared, but I have to take this step. You will never hear of me again. There is one last wish I have. Please don’t forget me, it’s my greatest fear. No one in real life will remember me when I’m gone, but with you people I have someone that cares about me. Please don’t forget me guys and let this be a lesson to you. Don’t Suffer in Silence. Don’t listen to others. Keep away from drama.

My biggest dream was to one day change the world. I wanted to be a person you can look up to, that helps people in need. I would have donated all of my money to a charity, but since my last money went down on the helium tank and the CPAP equipment, which I will need for a painless death.

Farewell brothers, make my dream come true and change the world.

It would be easy to reflexively read a suicide note such as this entirely through the lens of masculinity. One side could argue that this man is feeling this way because of this loss of connection to his manhood and his inherent masculinity. On the other side we can argue that this suicide note reflects a failure of masculinity. This man’s apparent attachment to masculinity means that he cannot cope or express his feelings and therefore is pushed to suicide.

I argue that there is something much more complex here however. What we can see is something much more that masculinity. Yes, this man clearly feels lost and purposeless, and this may in part be due to a loss of a sense of masculinity. But he also, as indicated by his text, feels deeply isolated from friends and family. He is disconnected from society more broadly, missing many of the social connections that are important for social life. Moreover, the very existence of this note contradicts any idea that he is so attached to masculinity that he cannot express himself emotionally, or that he rejects collectivity. The same can be said for the range of responses that follow notes such as these, in which other members of the space emotionally connect with the original poster either through trying to convince them not to go ahead, or through explaining that they understand and feel similar pain. In fact, we see this throughout many online male spaces, which are driven heavily by emotions and a sense of collective grief and pain.

While masculinity is part of the process therefore, it is not all of it.

I argue therefore that if we want to understand men today, and in particular if we want to understand the so-called ‘masculinity in crisis’ we need to explore issues beyond masculinity. This is true on both sides of this aisle – those who are part of the manosphere and those who are reacting against it. This is not just a story of a loss of manhood, or a sense of aggrieved entitlement because of a loss of power. It is much more than that.

We can see alternatives that engage with masculinity while also looking beyond it. Van Valkenburgh (2019) and O’Neill (2018) for example both situate the rise of manosphere, and other associated ideas within the context of the neoliberal restructuring of society. Both argue that neoliberalism represents not just an economic program, but also the extension of a “fiscally conservative economic mind-set into seemingly noneconomic spheres of life” (Van Valkenburgh 2019, p. 3). Van Valkenburgh (2019) for example examines members of Reddit subreddit r/TheRedPill, arguing that men participating in this forum have incorporated this “cultural rationality” to adopt an individualistic understanding of their manhood in line with neoliberal ideas. This process relies so strongly on neoliberal economic ideas, Van Vaklenberg argues, that when faced with problems men in this space are unable to turn against broader political structures, and in turn direct their attention inter-personally – targeting women as the key to their challenges. As he argues:

…faced with accumulating evidence of late capitalism’s negative economic outcomes – such as economic crises, alienation, exploitation, and unemployment – yet evidently unable to question capitalism’s supposed benevolence, the sidebar discourse enables men to divert hostility away from their surrounding economic system and redirect it onto women.

In her latest book, Wendy Brown (2019) argues similarly. Brown argues that neoliberalism – through attacks both on society and on democratic politics — has caused a rise in nihilism, coupled with an ‘accidental wounding of white male supremacy’. Both of these trends have resulted in the development of an apocalyptic politics, which often gets expressed through rage and violence from men. Brown for example looks at trolling online, arguing that trolling is what she describes as a ‘nihilistic form of action’:

The passion and pleasure in trolling and trashing are signs of what Nietzsche called “wreaking the will” simply to feel power when world affirmation or world building are unavailable. (Brown 2019, p. 170-171)

Brown does locate the rise of anti-democratic politics – one of the apparent symptoms of a crisis in masculinity – within a loss of power, or ‘dethronement’, of white men. This aligns somewhat with a version of the aggrieved entitlement explanation. She however expands beyond an analysis of masculinity, situating this sense of dethronement within the context of societal and political breakdown, alongside a rise of nihilism and resentment.

In both cases gender and masculinity are a core part of the analysis. But they are not all of the analysis. Changes in gendered relations, as well as shifts in the notion of masculinity, are connected deeply with other social breakdowns associated with the dominance of neoliberalism, economic crises, climate change and broad social shifts in our society. As Salter (2019) argues male violence doesn’t come from something toxic and bad that has crept into masculinity, “rather, it comes from these men’s social and political settings, the particularities of which set them up for inner conflicts over social expectations and male entitlement.”

To understand what is happening with men in spaces such as the manosphere, we need to look both at masculinity, but also look beyond masculinity. The narrative of a masculinity in crisis cannot do this for us.

This article is an expanded version of a presentation given at the conference ‘What We Talk About When We Talk About Crisis: Social, Environmental, Institutional’ hosted by the Australian National University (ANU) Humanities Research Centre in December 2019. You can contact the author at simon.copland@anu.edu.au