The story of the Knitting Nannas Against Gas and Greed (KNAG) begins in 2012. A handful of older women joined an anti-coal seam gas (CSG) group in Lismore NSW. They wanted to take action when the Northern Rivers area of NSW was being targeted for CSG mining by Metgasco, but became frustrated by the inaction and indecision of their male colleagues. The women were further annoyed by being asked to make teas and take minutes. Rather than stay frustrated through inactivity, the women devised their alternative activism as a form of ‘guerrilla surveillance’. Small groups went out into the countryside, parked by roadsides with their knitting, folding chairs, and thermoses to ‘scope out the works’; that is, watching, recording Metgasco truck movements (Ngara Institute, 2018). Initially knitting was a way of productively passing the time, but it soon became a form of environmental activism that older women could engage in. Determined to find ways of learning about CSG processes and impacts, the women went on fact-finding tours of the Chinchilla gas fields in Queensland, seeing landholders, farmers and families affected by toxic fugitive gases, contaminated water from taps and industrialised bush landscapes. They researched and shared their knowledge hoping to save the land, air and water for future generations.

KNAG use non-violent direct action, with a spin suiting the capabilities of older women. ‘Sit, knit, plot’ describes their formula for protest knit-ins at locations where they can be visible, talking with passers-by about the effects of fracking and fossil fuels on individuals, communities and environments. One of the original Nannas, Liz Stops (2014, p.10) wrote: ‘The name … was purposefully devised. “Knitting” and “Nannas” are words that immediately conjure a nostalgic image of older women exuding trust and love.’ Their ‘Nanna-ness’ is a form of strategic or tactical essentialism that communicates their identity and purpose with great clarity. Collectively, they refer to themselves as a ‘determination’ of Nannas.

Data from an online survey of members (2017) identify that the prime motivation for older women to join KNAG was the ability to participate in protests against coal seam gas, coal mining, and be vocal about environmental concerns more broadly in the face of climate change. Doing this through a woman-centred approach that suited the capabilities of older women in an active way (active ageing) was a significant attraction with some women mentioning the importance of learning. Many women said they saw Nannas at protests and were impressed by their form of non-violent direct action. Intergenerational equity and leaving a viable future Earth were initially a lesser motivating factor. Few mentioned knitting and crafting as an attraction! Additionally, most of the women who join KNAG groups (known as ‘loops’) are new to this form of activism, or indeed any activism (55%).

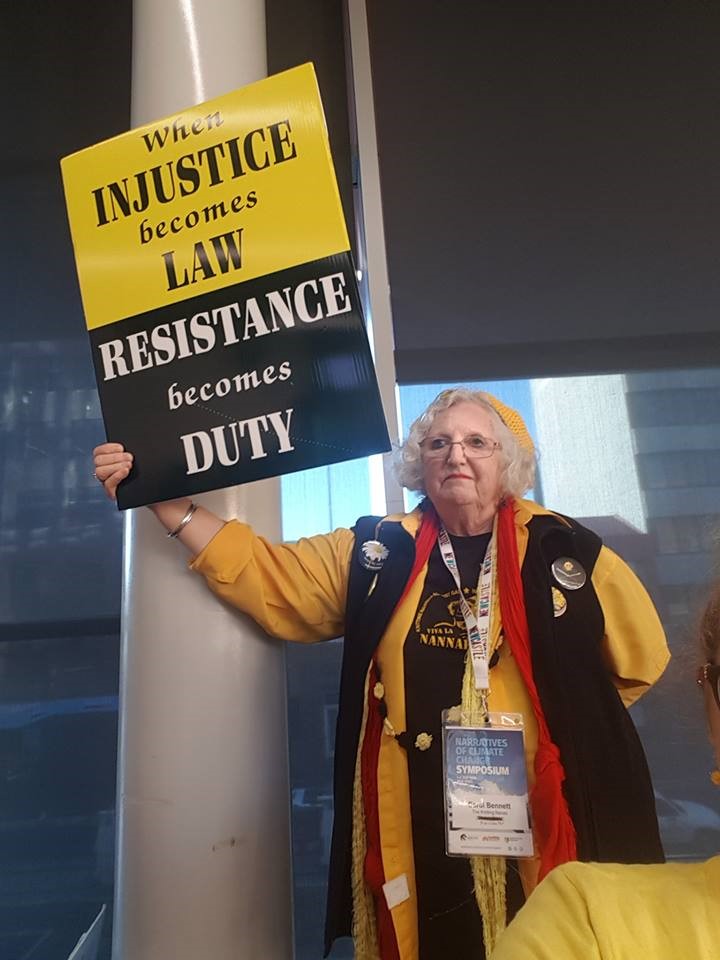

Figure 1: Nanna Carol Bennett (Gloucester KNAG) at Narratives of Climate Change Symposium, Newcastle University, July 2018, (Source: LJLarri reprinted with permission).

Purpose and crises

New members agree to adhere to the “Nannafesto” which states in part:

“We peacefully and productively protest against the destruction of our land, air, and water by corporations and/or individuals who seek profit and personal gain from the short-sighted and greedy plunder of our natural resources. We support energy generation from renewable sources and sustainable use of our other natural resources. We sit, knit, plot, have a yarn and a cuppa, and bear witness to the war against those who try to rape our land and divide our communities.”

“We want to make sure that our servants, the politicians, represent our democratic wishes and know they are accountable – to us. We are very happy to remind them of this – often. We represent many who cannot make it out to protests – the elderly, the ill, the infirm, people with young children and workers.”

“KNAG is not affiliated with any political parties – we annoy all politicians equally.”

The Nannas work to address a collection of crises. They highlight the crisis of confidence in politicians linked with corporate greed by demanding that the social contract and representative democracy be upheld (working for the people and not big business). By challenging misinformation and denialism with evidence-based research they contribute to their community’s understanding of climate science and the role of fossil fuel industries. By being visible and vocal older women they challenge sexist and ageist stereotypes. They support families in rural communities suffering the toxic effects of air, water and land pollution; townsfolk who realise they have been duped by mining companies and their politicians and emotionally fraught and frustrated younger protesters. Figure 1 shows Gloucester Nanna, Carol Bennett proudly showing one of her favourite placards protesting for democratic rights.

Crafty feminist project

Craftivism gives Nannas their identity and is a process by which they learn their activism. Wearing yellow and black, the colours of “Lock the Gate” anti-CSG movement, red to signify their support for

Indigenous First Nations, Nannas are easily and proudly identifiable as these quotes from surveys show:

“Cute little old Nannas knitting in uniform, not being scary, attracts a lot of attention, and those opposed to or not used to protesting are more comfortable.”

“It is such a good idea. Who is going to arrest a group of older women knitting outside a politicians office? Wearing black and yellow clothing.”

“Becoming more positive in myself about being ‘out there’ basically on show if you like.”

“Strength in numbers! A large group of single-focussed people is much more effective especially wearing yellow.”

In the case of the Nannas, craftivism emboldens and empowers older women to challenge gender and age-related stereotypes to become vibrant and central actors in the broader social movement fighting CSG extraction and fossil fuel mining, thus contributing to transitioning to low-carbon futures. In the process, they have also become part of the feminist project towards gender equality.

A significant element of KNAG identity is defined through crafting. Knitting, umbrella for all forms of craft, links KNAG to the worldwide craftivism movement, drawing on traditional female arts for undertaking social and environmental protest. Both craft and activism take energy and commitment, and as neither activity precludes the other, ‘activists can be crafters, and crafters can be activists’. Craftivism is a means for making connections between people who wish to live in a more just and safe world (Greer 2014; Fitzpatrick, 2018; Press, 2018). Drawing inspiration from women in the French Revolution, the Nannas use their crafting as a political statement.

The Nannas use their craftivism in all the different forms mentioned by craftivist and visual arts theorist Tal Fitzpatrick (2018). Examples include: Knot the Gate, the Nanna-version of Lock the Gate, leaving yellow threaded triangles across fracking well sites. The Nannas stage knit-ins outside local politician’s offices, soft handcuffs for symbolically linking Nannas at protests, knit berets, banners, sunflower badges and scarves in yellow and black as part of the Nanna uniform; wear character costumes like Brynhildr who wears a knitted horned Viking helmet and carries shield and sword (Figure 2); and make ‘Chooks Against Gas’, which are crafted soft toys representing chickens that are given away to children of families affected by toxic fugitive gases produced from fracking.

Figure 2: Brynhildr at the Beck Military War Museum, Mareeba, 2016. (Source: Reproduced with permission of MaryBeth Gundrum)

The media are catching onto the craft language of the Nannas. Illawarra Channel Nine TV News reporter Brittany Hughes talking about Illawarra KNAG knit-in outside local State MP, Gareth Ward’s office in March 18, 2019. said,

“Protestors have spun a yarn in the hope of unearthing the effects of underground mining. A group of Knitting Nannas gathered outside MP Gareth Ward’s office in Kiama today – calling to protect the region’s water supply. It may look like a peaceful protest but these women mean business … The group says residents are being stitched up

concerned [that] long-wall mining is affecting Sydney’s drinking water catchment which supplies water to 5 million people in towns such as Kiama.”

Craftivist and feminist historian, Lizzy Emery positions crafting and being crafty as “a methodology for touching the world with feminist hands” (2018, p. 1). This acknowledges that crafting and by extension, craftivism, is a primarily woman-centred activity and has potential to be a feminist enterprise.

“To craft is to make with feminist energy. To build. To build a world, an environment, a location. Feminist crafters craft in and of the existing world. But worlds that once did not exist are also crafted into materiality, into being, we craft feminist worlds. The practice of crafting, makes crafted spaces.” (ibid, p. 2).

A further connection comes from process-oriented practices of women-only participatory and relational art-making. Art historian Anne Marsh (2017, p.19) describes this “doing feminism” emerged in Australia in the 1970’s. She identifies craftivism as ‘build[ing] on a history of feminist practices amongst women’, including KNAGs as part of this continuum (ibid, p.16). Craftivism turns the domesticity of craft out into the public eye. This insight from interview with Nanna ‘Julia’ (2017) shows how it affects the crafter building their sense of agency,

“It’s not just knitting, it’s crochet, it’s sewing [or] it’s just creating silly things. I think the craft business side of things. It’s a way of building confidence in yourself that you can do something really little. Yes that can be symbolic, and I think that’s where the knitting comes in – it’s symbolism and also creativity. I think that’s what makes the Nannas really. We wouldn’t attract attention we’d just be another group to slam. But we use the craft of wisdom to bring humour into things to bring a self-confidence and a humour. Self-confidence to be able to actually feel that you know [about] doing something. It might only be little. I’m not much of a knitter but I do squares for the love wraps. You know the energy that I put into that is going out there right. And that’s the thing when you’re making things. Yes. You know you’re actually doing something that is a little bit creative might be small but you’re putting energy and love into it. And that in return gives you a satisfaction and confidence that you can contribute in whatever way is comfortable. A lot of Nannas that come in and they’re new [say] ‘Oh I can’t knit I can’t do this I can’t do that.’ And you’ll ask them ‘Well what do you do when you’re sitting at home watching television or what do you do when you’re out in the garden?’ They start thinking and inevitably they’ll come up with something they can make.”

Feminist and gender studies academic, Shoshana Magnet and colleagues (2014) draw on the ‘politics of kindness’ in their feminist approach to pedagogy. This relates well to the Nannas as they work their form of non-violent direct action through humour and evidence-based information sharing. They engage in what Magnet et al refer to as ‘micropolitics’ – ‘small acts of political engagement … on the level of bodily affect or cultural sensibility’ (ibid, p.8) which they say can mobilise political and social change. This is reminiscent of the very popular mid-1980’s feminist bumper sticker ‘Practice random acts of kindness and senseless beauty’. Coined by California-based writer, Anne Herbert in the ‘Whole Earth Review’ (July 1985) with the statement, ‘Anything you think there should be more of, do it randomly. Don’t await a reason. It will make itself be more, senselessly’ (O’Toole, 2017).

Feminist academic, Maura Kelly refers to Beth Ann Pentney’s description of feminist knitting as ‘active and purposeful … used in the spirit of feminist goals of empowerment, social justice, and women’s community building’ (2014, p.133). This signifies the work of KNAGs definitively a feminist project.

Figure 3: Sydney Knitting Nannas – 200 weeks of protesting against Santos. (Source: www.lockthegate.org.au Events October 29, 2019 copyright fair use)

Postscript

Eight years on and there are now around 40 KNAG ‘loops’, most in Australia, some in USA and UK. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lock-downs, knit-ins and presence at public rallies was regular practice. The Sydney Loop celebrated its two-hundredth weekly Friday lunchtime knit-in and public information presence in Martin Place on the first of November 2019 (Figure 3). They have dedicated their actions to challenging CSG mining company Santos whose offices are nearby. Not to be deterred, KNAG’s work continues online visible in social media and connected through their back channels they promote letter writing campaigns, online learning in climate action, Zoom meetings / protests amongst themselves (Figure 4) and those being held by other climate activist organisations.

“Zoom zoom a zoom a zoom zoom. We Zoom therefore we are. Or something like that…. #isoNannas are go! Nannas send their love to you all in iso land. #isowantagasfieldfreefuture #isolovecleanair #isothoughts #isomissgivingNannahugs #isowantarenewablesfutureforthekiddies #isowishpoppywouldbuymorewine”

Christine Milne, in her autobiography ‘Activist Life’ explained why her donation of Knitting Nannas Beret to the Museum of Australian Democracy, Canberra matters (2017, Chapter 9):

“Groups such as the Knitting Nannas … are authentic sparks of democracy fighting back against the plutocracy Australia has become. They gave people on the land a strong, loud voice at a time when they were feeling powerless, and they still do… They have been successful in stopping the expansion of coal seam gas in northern New South Wales but, as importantly, they have restored dignity and instilled courage into the ground-down. They have tapped into the deep well of country women’s strength and resilience and achieved what they set out to do. They are the ‘iron fist in the soft fluffy yellow glove’, forthright women in their prime and of their time.”

“The Knitting Nannas beret deserves one of the highest honours in conservation as it represents self-selection to take a stand for country, for the land. Knit in and knit on, Nannas.”

Acknowledgement: My thanks to the Knitting Nannas Against Gas and Greed, James Cook University and the Australian Government Research Training Scholarship for enabling this research.