– Translated by Louis Klee & Milena Selivanov

War and Poetry:

A Journey Through My Russian Roots

– by Milena Selivanov

I am writing from St Petersburg, Russia, where I have returned after seven years in Australia. This is my father’s hometown and it’s not my first time in the city. This time, though, I won’t simply be visiting, but living in the city.

When I visited St Petersburg, as a kid, I found it uninteresting since I had to stay indoors more than I wanted to. The apartment’s walls were covered in books, and I mean every single wall. Generations of my family have collected these books. And they all pointed to one particular person in my family, my great-grandfather, Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky.

All the stories I heard about him were from my grandparents, my great aunts, and my father. They were all marked by the domesticity of the events, which as a kid I found quite funny. What I never realised was that Vsevolod was born on the 10th of April 1895 and died on the 31st of August 1977, meaning he lived right through the major events of the 20th century: the First World War, the Russian Revolution, the Civil War, the Second World War, Stalinsim. And suddenly I see now how all the stories were deeply connected with the historical and political context of those decades.

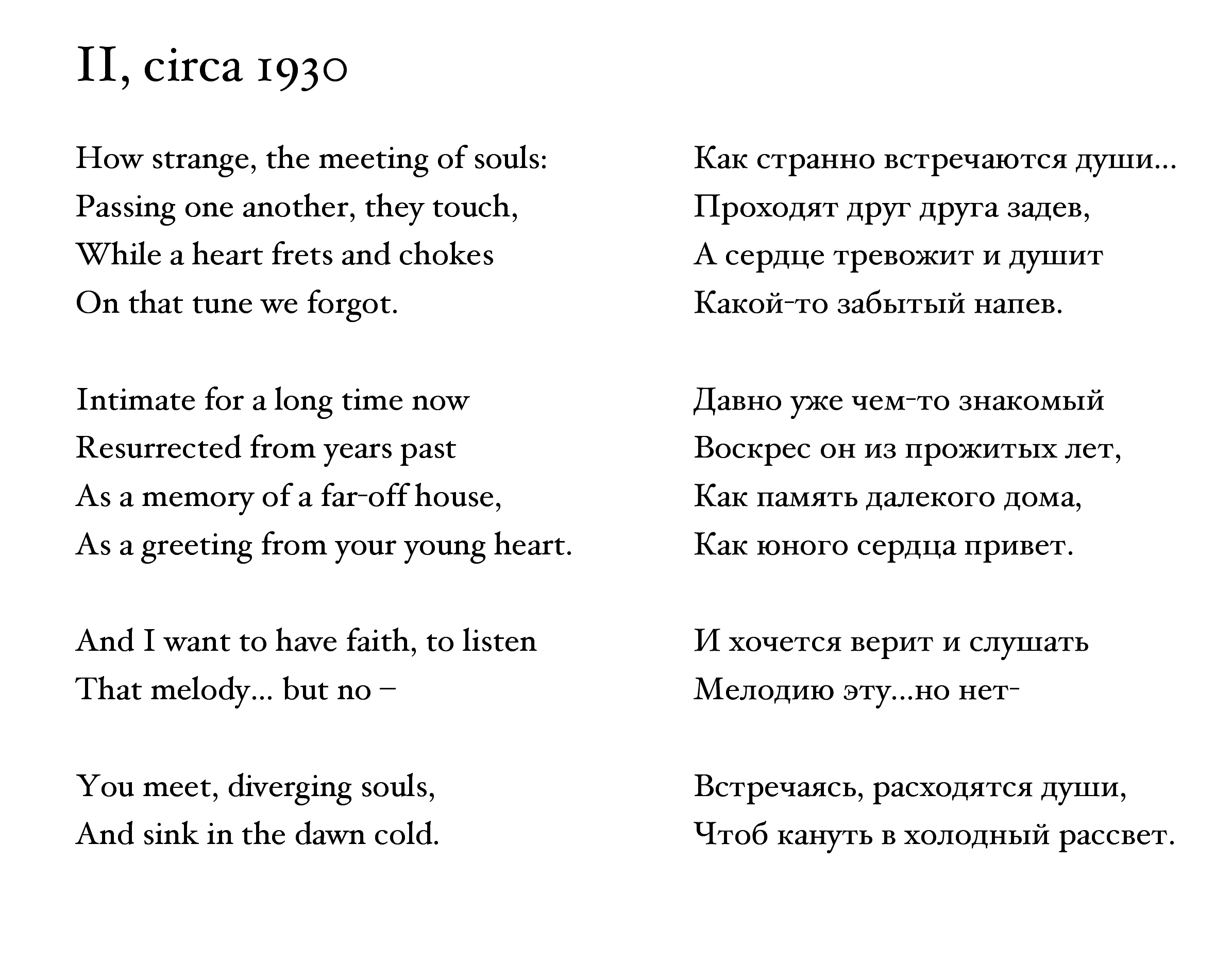

As a teenager, Vsevolod discovered his passion for poetry, and completed his university studies under the tutelage of Gumilyov, the founder of the Acmeist poetic movement, who was arrested and executed by the Soviet secret police in 1921.[1] In 1916, Vsevolod was enrolled in the army to fight in WWI. He was still an official in the Tsarist army on the 25th of October 1917, in the decisive months for the victory of the communists driving Russian Revolution.[2] He was taken hostage by the Red Army on the night the Russian Empire fell. He then enrolled in the Red Army, but at the end of the day, whether the arm he served her tsarists or the communists, his main aim was to keep a roof over his head and food on his table. Thus, as his name started to become nationally renown in the early 1920s, he left the army and was able to dedicate himself to the profession he loved: poetry. This was at the time Stalin was rising to power.

In 1941, Vsevolod was called to the military service again. Leningrad, as Saint Petersburg was then known, was under the notorious siege and every child and mother had been evacuated on trains to the country, away from the war. Among them was my grandmother, aged 4. Her father remained in Leningrad, working for the army’s newspapers until the end of the war in 1945. Historians consider the Eastern Front, and Leningrad in particular, to have suffered the greatest civilian loss in WWII. After the evacuation, the city had 1 million people left. At the end of the war, a sixth of the original 3 million were still alive.[3]

With the end of WWII, Vsevolod was able to dedicate himself to poetry again. He was part of the committee of Soviet poets and writers, and he lived in an apartment block that was assigned for the society’s members, meaning he was surrounded by the many of the finest Russian poets and writers who lived in St Petersburg at the time. He wrote lyric poetry, and was in this respect quite different from thetrend of poetry at the time, which were fixated on socialism and social justice. But living in these quarters was no literary party. The poets had to live in close quarters with others of different personalities and diverging political interests. As story has it, my great grandmother (Vsevolod’s wife) smuggled three volumes of a four-volume edition of Gumilyov’s banned works across the Russo-Finnish border. My great grandfather was at times accused of political conspiracy for this type of inconspicuous behaviour. These claims were never verified. But it clearly shows that you had to be careful about who you knew, what you wrote, and where you went because someone was ready to point a finger at you. Gumilyov’s three volumes are still standing in one of the library’s shelves.

The two images that strike me the most are two of my father’s memories of Vsevolod. The first is the reminiscence of the poet’s room and how he could not see beyond his arm’s length. Vsevolod could only work when the room was filled with tobacco smoke. And the second relates to his death. Vsevolod died while signing off his last poem.

Now, I believe the story that I am sharing with you about Vsevolod should not be taken as fact. Not because it is not true, but because I have never met this person, and the stories and impressions that I get about him are gained through those who knew him. All that remains that merits the term ‘fact’ are his poems.

But then what is the point of learning and remembering one’s family history? Ultimately, I am persuaded that their stories inspire us to play a role in our modern society. The problems that my great-grandfather faced were, no doubt, very different from today’s problems. Yet, his dedication, his passion, and human character inspire me to pursue what I am interested in and stand up for what I think is right. One’s roots can play a powerful role – they drive change through those who give them a voice. By exploring, experiencing, and becoming more rooted with my origins, I hope to better understand what kind of person I am and how I should carry out my responsibilities in life. Do not forget where you come from. In the end, who we are now is an intertwined figure of who those before us were, and how their past actions influence our present and future.