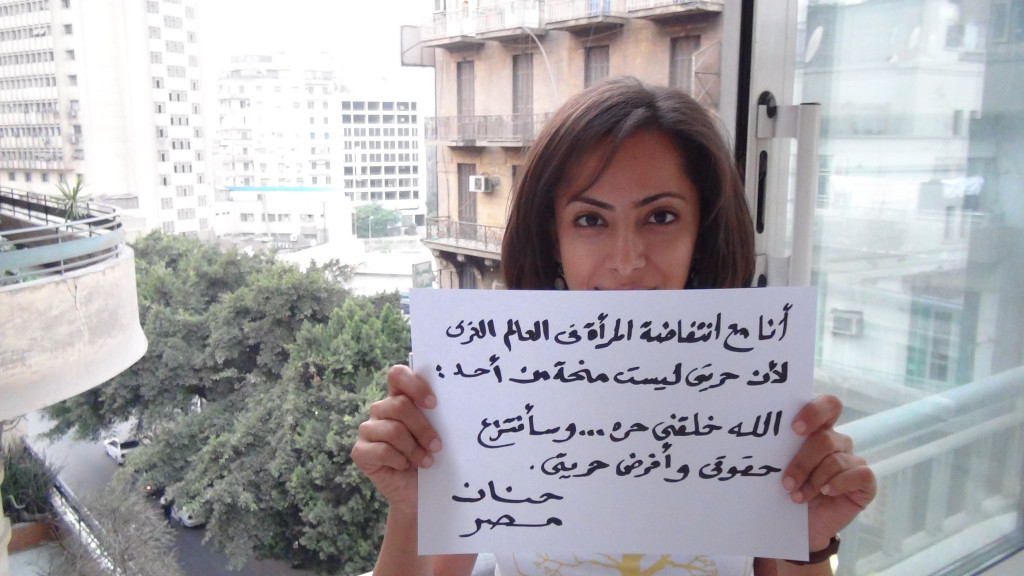

Hanan, from Egypt holding a sign reading: “I am with the uprising of women in the Arab world because my freedom is not a gift from anyone I was created free and I will take my rights and impose my freedom.”

The online remains a yet unchartered, ungendered space. A woman blogs from the privacy of her own home, perhaps anonymously, and there is the potential that her words will reach thousands like her. She therefore personifies the paradoxical, unlikely, but very real fusion of public and private in the modern era. In the context of the Middle East, this outreach is unprecedented and transcends traditional spatial, social and gendered boundaries.

Women’s movements in the Middle East have taken on the form of what Bayat terms ‘fragmented activisms’, which are piecemeal, idiosyncratic, and everyday acts of resistance that may collectively lead to a tangible outcome.[1] Drawing upon the binaries of public and private, West and East that permeate the discourse, this paper will demonstrate the shortcomings of traditional theoretical divides when applied to women’s activism in the Middle East. While many women were physically present and leading mass-demonstrations in public spaces during the Arab Spring, this paper will focus on the way social media and hashtag activism is enabling a more fluid, hybrid and meaningful form of social movement for women in the Middle East. It will consider whether the Western origins of online activism undermine the authenticity and autonomy of these grassroots women’s movements. It is important to note the diversity and richness of women’s experiences across the region – the experiences, civil rights and liberties of women in Egypt are vastly different to those in Saudi Arabia. Nonetheless, the structural marginalization of women holds true in the Middle East and around the world, where social, political and religious institutions have (to varying extents) compromised women’s self-determination, identity and potentialities. The ascension of the online space is shifting the parameters and potentialities of social movements, though crucially, it is not social media that is singularly driving change. Ultimately, change remains contingent upon the agency of women in the Middle East.

The Western understanding of social movements has traditionally valorised coherency, public defiance and mass-demonstrations to the exclusion of the alternative forms that protest may take. In many ways, the Arab Spring of 2011 conformed to the Western model, and was celebrated and eagerly tracked across the Western world as the ‘Spring’ of modernisation, liberal ideas, grassroots democracy, and a definitive shift in regional activism. Prior to this, the model for activism in the Middle East was of the lone, educated elite – ‘these “citizen journalists”… eschew[ed] the creation of formal organizations that might draw unwanted attention from the state.’[2] Yet, the very characterization of the Arab Spring as the turning point of activism, or indeed as an evolution of existing movements, diminishes the authenticity of movements that fought for social equality in the region prior to 2011. It is symptomatic of the ‘universalizing tendencies’ of the Western lens[3] in its implication that only movements that follow the Western trajectory of progress and modernization can be legitimate.

Critically, the East/West binary is destructive on both sides of the discourse, and its use is often more about political expediency than a reflection of truth or fact. The label of the ‘West’ has also been used to internally discredit Arab feminism when it is deemed to be too liberal or secular in character. As Lila Abu-Lughod asserts, ‘those who claim to reject feminist ideals as Western imports actually practice a form of selective repudiation’,[4] where otherwise useful arguments might be discredited or undermined solely on the basis of their perceived ‘Western’ character. Scholars such as Talal Asad have illuminated the need to move toward a more hybrid, holistic approach that rejects diametric binaries when considering West versus East, secularism versus Islam.[5]

The construction of the autonomy of Arab women through this Western lens has been highly selective. Individual examples have often been made to fit neatly within the overarching Western narrative of progress, and adhere to the Western model of movements – for instance, Ibroscheva has explored Western popular media coverage of first ladies in the Middle East, finding that ‘their seemingly intuitive connection to the West’[6] was emphasised and praised. Prior to the Arab Spring, they were solitary beacons of elegance, glamour, political empowerment and refinement – exceptions from the seemingly oppressed majority of Arab women. However:

[T]he events of the Arab Spring almost overnight transformed the Western views of these popular faces of female political power from embodying the potential to “modernize” the Middle East into symbolizing the oppression that triggered the people’s discontent in the first place… the popular media essentially created a simplistic dichotomy of political choices which obscures the complexities of gender as a legitimate marker of democratic

development.[7]

This Orientalist narrative fetishizes the Middle East as inferior, exotic, and backwards. There is a normative assumption that Arab women experience false consciousness, and often there is a problematic conflation of oppression with Islam, thereby holding religion or culture singularly culpable rather than acknowledging the role of the governing state apparatus.[8] As Yadav rightly identifies, this is particularly true in the construction of Arab women’s activism ‘when such activism is oriented toward goals that do not promise women temporal equality with men and have substantial consequences for the nature of public politics’.[9] This predisposition was confirmed in Al-Rawi’s study of the Facebook comments of three key online feminist movements (‘Uprising of Women in the Arab World’, ‘Girls’ Revolution’ and ‘Revolution against Patriarchal Society’). Each of these movements supported gender equality in the Middle East, and the study found the discourse to be permeated with misconceptions from both Western and Arab commentators.[10] Ideological backgrounds played a big role in construing controversial issues such as the veiling of women. As Scharff contends, ‘crucially, the trope of the ‘oppressed Muslim woman’ is intertwined with the construction of ‘western empowered selves.’[11] This binary of East and West is clearly problematic, yet constantly reinforced through the essentialisation of the Middle East, where the values of the Middle East are made malleable depending on which Western agenda is being advanced.

The inadequacy of Western models when applied to non-Western contexts, as well as the creativity of Arab women’s movements, is illuminated when we consider Bayat’s idea of a ‘non-movement’.[12] Bayat argues that the Arab women’s approach (particularly in countries such as Iran) is alternative when viewed through the Western lens, but is in reality subtle, everyday, but still meaningful. He writes:

[A ‘non-movement’] involves deploying the power of presence, the assertion of collective will in spite of all odds, by refusing to exit, circumventing the constraints, and discovering new spaces of freedom to make oneself heard, seen, and felt. The effective power of these practices lies precisely in their ordinariness, since as irrepressible actions they encroach incrementally.[13]

Essentially, Bayat stresses that even ‘mere’ presence is both constitutive and powerful as it has a cumulative and symbolic effect over time. A woman’s ‘mere’ presence in a public space also challenges problematic binaries that regard the public as a predominantly masculine sphere and relegate the feminine to the private. After all – ‘intimidation by regulation of the public space is intimately tied to social control of identity. Women’s mobility in terms of identity and “their place”[14] in the public space are closely connected.’[15] Micro-level social change can be particularly effective in societies where the overarching socio-legal framework cannot be openly challenged in the way that Western institutional structures can be.

This idea of presence has powerful implications when applied to the online sphere and social media has complemented and redefined the terrain of existing activism in the Middle East. The online is increasingly a site of political struggle, where individuals and institutions use social media to project their voices and expand their sphere of influence. Unlike anything before it, ‘the Internet is a medium that facilitates self-representation.’[16] For this reason, the increased freedom of speech afforded by hashtag feminism and online activism more broadly, symbolises for Arab women in particular a way of moving past the disapproving gaze of society and expectations of duty and silence, in favour of actively engaging in the public dialogue in an unfiltered way. Yadav ‘measure[s] the ‘publicness’ of an act by its intent and its effects, not its spatiality.[17] In effect, social media and hashtag feminism amplifies the publicness of women’s actions. Though statistics show that women in the Middle East only make up one third of online presence, this remains a relatively high proportion of representation in light of structural challenges to the expression and publicness of a woman’s actions.[18] Despite the proportionately unequal presence in the online sphere, it marks a decisive change.

Though it has been argued that ‘online politics and material social movements are not ontologically different activities but rather different modes of being political’[19] this existential characterisation translates into something very different in the analysis of women’s online activism in the Middle East. Context is both essential and constitutive, and online politics and female web activism take on a greater significance in the context of the Middle East simply because while the objectives of online activists may be the same as those physically protesting, the visibility and scope of outreach are vastly different – they constitute very different methods of empowerment: the online, here, broadens women’s opportunities to assert their agency and contribute to a dialogue they may have otherwise been physically crowded out from. Indeed, while ‘young women were relatively less visible in the streets and physical public squares prior to the Arab uprisings, they carved out a robust, participatory, and leadership role in cyberspace during the Arab uprisings.’[20]

Taken together with the Western dominance of social media, and the Western origins of online activism, it is relevant to question whether the autonomy and authenticity of Arab women’s online activism is undercut or compromised by its Western influences. Islamic feminism, though sharing common themes and concerns with Western feminism, is not subsumed within it due to the unique role of Arab-Islamic religion, history and culture which endow otherwise equivalent acts with different significance. Just as feminism is not exclusively Western, but ‘something universal that finds particular forms of expression in different societies’,[21] women’s online activism in the Arab Spring (and in the time since) is just one manifestation of the overall movements of online activism in pursuit of civil rights and gender equality both in the Middle East and worldwide.

It is also worth considering the favourable way in which women’s online activism during the Arab Spring has been portrayed in the West. Arguably, the reason for the widespread approval and encouragement is because it conforms to the Western model of activism. With a discourse of progress, large outreach, and a more direct and conventionally proactive form of activism, the Arab women’s online movement aligns with Western approaches. In so doing, Arab women have generated solidarity, awareness and media coverage within their regional sphere and internationally.

On the other hand, the act of hashtagging and making status updates on social media is so commonplace that in some ways, it does fall into Bayat’s idea of non-movements and fragmented activisms. Twitter hashtags can be considered an example of the most fragmented of activisms; a lone tweet, an online manifestation of an individual thought, is as susceptible to completely disappearing into cyberspace as it is to being publicly promoted. But tweeting may also be inherently public, and political. The subversiveness of hashtag feminism lies not even in the controversial or politically outspoken nature of its content, but in the very potential that it has, and in its very presence. When this potential is activated, we see that where non-movements constitute subversion in a quietly political way, hashtag feminism is subversive in a more blatant way. There is something about social media that thrives with potential, and that potential can grow into significant momentum if it finds coherence and resonance in a wider social movement, as with what happened with the Arab Spring. In this sense, unthreatening every day activities can through presence alone (in this case, online presence and engagement with that dialogue) effect long-term social change. Essentially, using Twitter is itself a passive act in a public space, much like a fragmented activism or non-movement. When this use is married with a political objective, the act itself remains passive, but this online expression of discontent heightens the political character of the action. Moreover, hashtags are necessarily instruments of connectivity in the Middle East, where women may otherwise find it difficult to immediately engage with such a large network of like-minded people.

One critique of hashtag activism is that while it encourages the agency of women as contributors to the conversation, actual change cannot be effected unless the powerful listen. However, in perspective, this is not so different from physical mass demonstrations – while the force and the visuals of a vast crowd of demonstrators is intimidating, without concessions from the government or the military, legislative and political change will not necessarily come about. Both online activism and traditional social movements rely on individual agency and assertiveness, but also on mechanisms of power taking note of such assertiveness.

This paper has explored the necessity of moving beyond the simplistic binaries and tropes that pervade the discourse on Arab feminism, women’s social movements, and the apparently irreconcilable divide between Islam and the West, public and private. Women’s online activism in the Middle East epitomises this new fusion of binaries in the way that it overcomes traditional distinctions through dialogues within the Middle East, while also engaging the West, and also in the way that it bridges the distance between otherwise geographically disparate, and perhaps even ideologically fragmented voices.

While it is true that social media sites such as Twitter (and the hashtag feminism it has facilitated) have been important in the West in unifying otherwise disparate and marginalised women, women’s online activism takes on a new dimension in the Middle East, due to substantively different cultural norms, historical development, and religious moral codes:

It is the dialogical content of these media rather than the positions represented therein that must be appreciated and recognized as instrumental in lending support to democratic struggles in a region that has until recently been distinguished by a media order in service of failed or authoritarian states.[22] [Emphasis added]

Equivalent acts, after all, take on different meanings depending on context, and the fact that the dialogues are now occurring in the fused online public/private space in the Middle East, is a meaningful step. For those in the Middle East, it is important that their activism is not swept beneath an overarching Western narrative – Middle East feminism is not something externally imposed upon the region; it is not ‘borrowed, derivative, or “secondhand”’[23] and to characterise it as such is belittling. As for continuity and enduring impact, ultimately, the success, legitimacy and authenticity of women’s movements everywhere centre on their agency and sustained capacity for self-determination.