Technology is making us robots.

It feels like an absolute cop out to begin a piece by gesticulating about the age of technology – but hear me out.

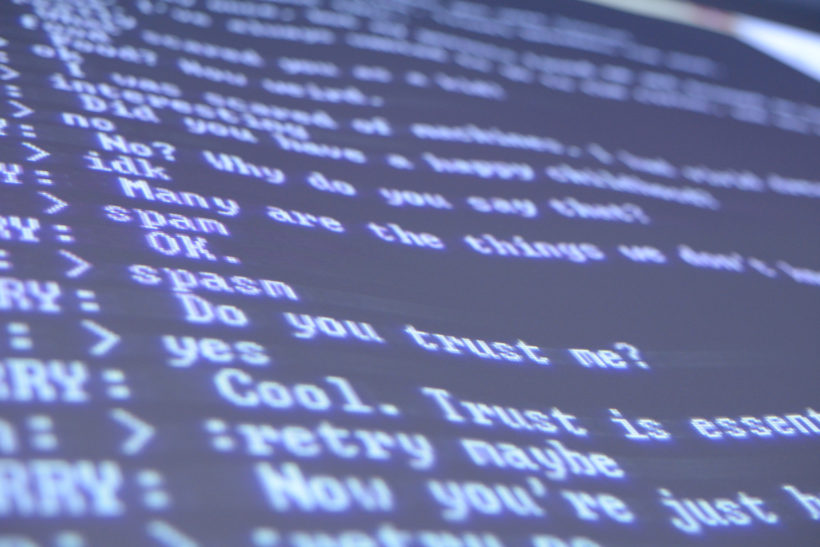

In a recent media consumption frenzy, I came across RadioLab’s recent experimentation with the Turing Test which investigated the ability of chatbots to masquerade as human, catfish vulnerable singles online and bring down US presidential elections. Their ultimate findings, derived from a charmingly alliterative game entitled “Robert or Robot?”, determined that over the course of the last seven years chatbots have become significantly more adept at replicating human speech – so much so that almost half of their live audience weren’t able to distinguish a chatbot from their beloved radio presenter.[1]

As a philosopher of language, a teacher of young people and a perpetual over-thinker, the implication that incessant engagement with technology was rapidly shaping our communication seemed a revelatory and enlightening proposition. Significantly, for the purposes of this publication and to the satisfaction of my own mind, shifts in modes of communication often entail shifts in power dynamics and, thus, impinge on the positions or roles of bodies in society (Waylen et al. 2013).

A brief and completely unscientific survey of modern discourse would seem to suggest a distinct shift in, or perhaps a renaissance of, consideration of the body as political (what ‘wave’ are we up to now?).[2] That is to say that, concerns about the very real effect that microaggressions, oppression and systemic discrimination can have on a body are being brought to the fore through conversations about race, invigorated debates about gender roles and sexual trauma and the push for a more inclusive realm of public discourse.[3] The aphorism ‘stress is bad for your health’, for example, is given new weight as a result of these conversations and becomes particularly stark when placed in contrast with a wellness culture epidemic, the attainment of which is typically only accessible to the white and upper middle class.

Increased visibility of these issues is positive, if not a little condescendingly scientific at times, considering the very real experiences felt by bodies that are othered. The central concern of this work is, however, that when these studies, issues and consideration are brought into the public sphere, they are treated with rhetoric that enforces conceptions of mind-body which will ultimately stall or slow inclusive social movements. If, as the team at Radiolab suggest, the use of technology is influencing our communication to become more robotic and systematic, public discourse may forget the subtleties and obscurities inherent in issues relating to the body and this may create spaces that accept a continued discrimination or othering of certain bodies.

The ‘weathering’ hypothesis.

Established by Arline T. Geronimus, Sc.D. Harvard School of Public Health, the weathering hypothesis (Geronimus et al. 2006)has been picked up in recent years by a range of publications contributing to this centring of discourse on the body as political.[4] Put crudely, the hypothesis suggests a strong relationship between the experiences of socioeconomic oppression and poor health outcomes over time. Creating a clear link between the vulnerabilities of the body and experiences of discrimination (systemic or otherwise) provides powerful ammunition for movements of inclusion and acceptance. Without careful treatment, however, discussion of this hypothesis may quickly turn to the presentation of a causal link between the mind-body. That is, the experiences of life as an oppressed body cause the stress experienced by the mind which, in turn, place the body at risk. This may enforce a separation of ‘me’ and ‘my [black/female/othered] body’, paving the way for exchanges that valorise the experience of these hardships as constitutive – as an ultimately ‘good’ experience rather than something that is reprehensible. The rhetoric at once allows the space to contemplate what life would be like outside the systemic oppression and fails to fully harness the power of the argument that psychological stress is a physical oppression, a very real harm to the body.

Experiences of a different body.

In a related turn, Virtual Reality is perpetually heralded as a way to build or promote empathy for the experience of diverse bodies (Bertrand et al. 2018; Maister et al. 2015). At work in these investigations is the suggestion that through the transmutation of the body, or the transference of the mind, one’s experience of existence and understanding of the world is shaped.[5] This experience could be carefully read to suggest that the inhabited body not only shapes one’s psychological experiences but constitutes them. However, the impact of these studies is effective because of the temporary shock that is experienced. That is to say, one is able to build empathy for the other because one’s mind is not actually going anywhere – the experience being had is by, for example, a ‘thin’ body that perceives itself as a ‘fat’ body temporarily. If it were actually to become a fat body, the need for empathy with the other may no longer exist, or more probably, there would be a whole host of other thoughts, feelings and prejudices that it experiences. This is problematic because of the associated implication that by simply being in someone else’s body, I might come to fully understand their experience. Rather than actually speaking with the other, listening to them, trying to understand, or simply believing what they say is their anguish or pain, I can simply transport my mind and see for myself. Sitting with the discomfort of not really knowing but still choosing to believe the other may prove too much of a stretch for a world and system of communication defined by developments in technology.

‘On Being In Your Body’.

Technologists are not the only ones exploring positive actions in response to psycho-bodily trauma. The work being done by artists such as Caitlin Metz and Victoria Emanuela to heal and unpick some of the damage done by experiencing life as a particular kind of body is arresting in its radical vulnerability.[6] Through the creation of infographics, activities and dialogue, these artists create a space and an opportunity for people to connect with others who have experienced trauma and build unique pathways for thinking about or experiencing their life and their body. The promotion of a clear and open recognition of trauma as affecting a dissociation with the body is important, especially considering the potential of ‘weathering’ as discussed above. Although their careful use of inclusive language leaves space for bodies of all kinds to engage in their work, the act of ‘reconciliation’ presented in these artefacts maintains connotations of the meeting of two separate things: the mind and the body. Even as I write this, as I examine their title, ‘On Being In Your Body’, I struggle. To say one is in your body is to say that you are occupying something other. To say it is your body is to create a relationship of ownership that entails a kind of responsibility, much like one has over a pet. The possessive is ill-fitting here. The fissure represented by the hyphen of the mind-body problem presents a gap through which arguments, pauses and protests may fall.

Dualism persists.

The discomfort I feel in relation to each of the fields described above is in the perpetuation of rhetoric that allows a continued dissociation with the body. If left unchecked, the perceived causal relationship between experiences of ‘the mind’ and ‘the body’ will become established. At surface level, this could be considered beneficial for movements of inclusion with the establishment of a clear connection between psychological distress and physical harm. However, if unchecked, it may perpetuate compartmentalised remedies that seek to, for example, merely placate the stress felt by certain bodies rather than working towards broader social change; or suggest that simply by being insomeone else’s body, one might come to fully understand their experience and are thus able to make informed decisions on their behalf. These propositions are best left for the creators of Black Mirror to tease out and scare us with, but as developments in AI come ever closer to passing the Turing Test or as we come ever closer to computing rather than communicating, I can’t help but worry that we will begin to simplify conversations about psychological and physiological experience. If our use of language lets us down in the treatment of these ideas, it may provide openings and spaces through which we can crawl away from the discomforts or realities of bodies. Without a question of what life as a body is, we may only temporarily reconcile ourselves with it, precariously admiring its static form and perpetually ready to be dissociated from it again as it changes.

On Being Your Body.

It is worth, then, more carefully considering how public rhetoric may shape our understanding and approach to matters of inclusion, acceptance and recognition. I am not sure that I am ready to fully adopt a monistic approach to the mind-body problem and I doubt that working to establish one position over another is likely to radically alter persistent and systemic discrimination, but I am interested in complicating the issue when it arises.

After all, I am my body.

Or, at least, I am.

And that should be enough of a reason to stop aggressive, discriminatory or dismissive actions against me. And you.

Bibliography

[1]Surpassing Turing’s prediction by 20%. For more information about Turing see Moor (1976) and French (2000), see the Radiolab episode here.

[2]See Butler (2011), Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex.

[3]See #MeToo and Mendes, Ringrose, and Keller (2018), Black Panther and Dargis (2018), NPR’s Code Switch, The Fat Studies Reader by Wann (2009), ‘Think disability is a tragedy? We pity you’ by Janz and Stack (2017), Trans and Marriage Equality movements (Pitts et al. 2009; Anderson, Georgantis, and Kapelles 2017), and the changing examples set by popular culture (Waddington 2018).

[4]See Strauss (2016) and Norris (2011).

[5]It must be noted that maintaining a critical viewpoint is essential when examining research which may be caught up in the fight to present ‘positive’ technological advances due to the inseparability from economically driven pursuits.