Sometimes resistance is not violent. Sometimes, it is reinforcing what is peripheral to a culture because the roots of it are still in the homeland. The Kashmir Valley, at the foot the of the Himalayas, endures both kinds.

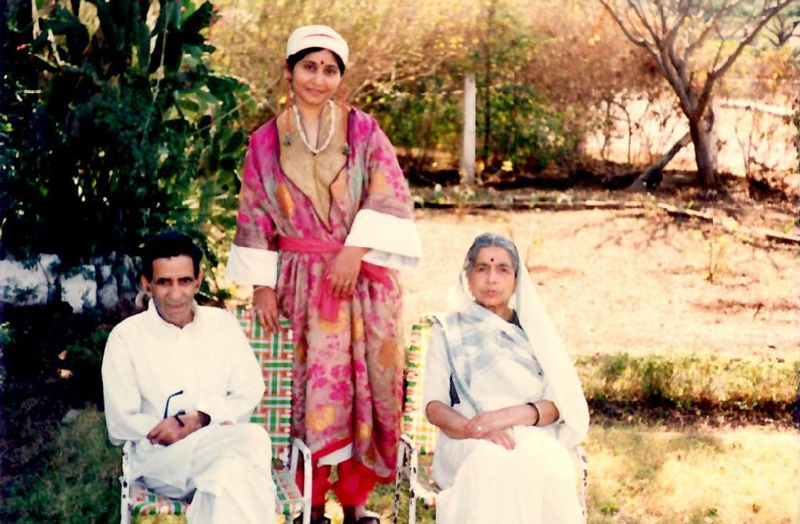

My family, as far back as we can trace, are Kashmiri Pandits. They inhabited the Kashmir Valley since a time predating Mughal Rule, British colonisation, partition, geo-political rivalries, hegemonic intrusion and repression from multiple state actors. They lived in a Valley that embraced the beloved Kashmiriyat- an indigenous multiculturalism- a fusion and celebration of all religions and tradition.

The story of Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmir as a whole is one that cannot be told through a single narrative. Life for those still in the Valley is heavily militarised, serving as a backdrop for violence, trauma and sexual assault. Life for those outside the valley is often one of mere existence, silence and cultural erosion. The Valley survives resistance movements, indigenous movements, separatism or terrorism… call it what you will. But the generation that is growing up there now, my would-be peers, have inherited loss and rage, been stripped of their autonomy and do not know Kashmiriyat.

The exodus of Kashmiri Pandits has reduced my community’s struggles to a separatist vs patriot dichotomy. It has reduced the wider population of the Kashmir Valley, a majority Muslim region, to religious extremists, Indian nationalists, or Pakistan sympathisers. Yet all groups are unified by the reminder every day that their culture, their practices and their very sense of communal existence are fading away because the Valley as it once was becomes a blurred memory. Pandits often feel like “refugees in their own country,” which strengthens the separatist vs patriot dichotomy, necessitating unwavering loyalty to India. This is in spite of subsequent administrations politicising their struggle and fighting separatists in their name, whilst simultaneously neglecting the Pandit diaspora’s needs.

Even the way we are referenced as a community: the exodus, exiled or Pandit diaspora seems to signal an ambiguity around how many Pandits were compelled to leave the Valley, who compelled them to leave, and how many have returned. What adds to this ambiguity is that there is no word in Kashmiri that encapsulates what the Valley means to all Kashmiris, and no exact explanation of how the diverse melting pot of religions and practice create Kashmiriyat. Rather, it is only something that can be expressed in a language communicated outside of the spoken word, subtle actions with obvious significance.

Language and Loss

“Saine shure chineh vane Kashir basiyan”: Our children don’t look Kashmiri anymore.

This passing comment in Kashmiri from a distant, Kashmiri aunty (although what actually constitutes distant in Kashmiri families is a contentious topic) has resonated with me.

What did she mean? Did she mean we are darker than the traditional “fair” skinned Kashmiri, because the community now have to live in sunnier parts of India and abroad? Was it lamenting that we had adopted hybridised Indian/non-Kashmiri-Western dress sense? Or was it dismay that the mother tongue of my ancestors was being lost or evolving from the original language used to convey their traditions so unique and specific to their beloved homeland?

The loss of the mother-tongue within the Pandit diaspora is a source of great sadness for the mothers and fathers that grew up with this as the language of familiarity and comfort, connecting them to all descendants of the Valley. Language can be both the greatest tool and hindrance in communicating their deepest traumas and their gravest losses. Now that English and Hindi have replaced Kashmiri, how can there be inter-generational communication and acknowledgement of our community’s history? It is a language spoken with a special contortion of the tongue that explains why so many who fled the Valley were ostracised and “otherised” for their Kashmiri sounding Hindi accents in the rest of India. Explaining this to their children, in a language different in its execution to Kashmiri, usually garners no more than a perfunctory nod and the obligatory acknowledgement. I too am guilty of this.

The older generation holds onto this language, a language so inextricable from their homeland. Speaking the language reminds political administrations that our histories cannot be minimised in pursuit of a simple military solution that keeps us “safe” from the Valley’s violence. So I think when my aunty commented so casually what she did, what she really meant is that we don’t “sound” Kashmiri anymore. And because of this, our comprehension and articulation has not grown through the Kashmiri language. So we don’t “look” like we have absorbed the psyche or lived the identity.

My cousin, born outside of Kashmir, admitted that aside from her wedding day when she allowed the aunties to relish in Kashmiri traditions, she preferred to be “normal” every other day. Inadvertently she brushed over centuries of tradition, diminishing how crucial the performances of these traditions were in order to preserve a legacy left behind.

Culture is not immutable, and traditions naturally evolve. Yet for the Pandits, their own children acknowledge these in such a passive sense. Alongside exodus, my community is now enduring the inevitable cultural erosion. As this erodes so too does subsequent generations’ connection to a Valley so far away, and in my case, unseen.

Recognition

When my uncle parked on the side of the road by McDonalds in Delhi-I use the term park very loosely- I did not expect to witness a subtle yet unsettling reminder of what it means to feel “otherised”.

The parking instructor, an elderly, thin, severe looking man leapt up at once and approached our window. Even by Delhi standards, the standard of my Uncle’s park was questionable. As he knocked on my mother’s window, he began the well-deserved admonishments, talking for at least thirty seconds before I realised my mother was smiling and gazing at him intently.

“Tohay chiv Kashir basiyan”: You look Kashmiri.

My mother had absorbed just one thing from the parking inspector’s words, and that was his sound, thus by extension, his identity and his history. At once the previously stern man broke out into a smile and the next ten minutes were spent, unsurprisingly, discussing the Valley, their families, weddings and where his daughters now lived. Tellingly, the first words my mother uttered to him, to identify him, were that he “looked Kashmiri”. In light of what my aunty had said earlier however, what they both really meant, is that he spoke Hindi with an accent that immediately summoned his history in the Valley; that he had lived the Valley’s realities, inherited the cultural legacy and was inextricably linked to the psyche. He, like her, was an “other”.

My cheeky mother wasn’t about to pay a parking fine (what an act of defiance)! More significant was the everyday resistance that I witnessed. They continued to remember a time that sits outside a simple narrative, a homeland that celebrated Kashmiriyat. This memory will not disappear because of violence and mismanagement. Violent Kashmiris and military responses can undermine my mother’s physical connection and safety in the homeland, but neither can erase the memories of a culture and tradition that endures.

Compensation and Consumption

Food is central to Kashmiri gatherings, representing a safe and familiar mechanism to preserve the culture. By no means is it a calm affair- the aunties decree that the “recommended” serving size is harmful propaganda, the uncles dare not argue with their wives, and the youth dare not refuse a sixth helping. When this community fled the Valley, they lost the ability to easily perform their culture, because of it is inextricable link to the homeland. The emphasis on food is a method of preservation, emerging from the physical disconnection with the Valley.

When visiting my Kashmiri family in various parts of India, even as a young girl, I could not overlook the tone of melancholy in which their homeland was remembered. Obscure and seemingly dispensable conversations were underpinned by a deep yearning to relive the times they had in their homes, at the foot of the Himalayas. In one particular instance, I accepted some almonds from a family member who then lamented that these almonds were nothing like “Kashmiri almonds”, and that they could not get those almonds anymore. This triggered an unexpectedly profound discussion of the foods they no longer had, or quality of produce native only to Kashmir.

Now no longer available, the taste and textures of these foods exist only in their memories. The absence of seemingly trivial items reminds them of a narrative they did not choose.

Return and Resistance

“Ghar Vaapsi”: policy of Pandits’ en-mass return to the Valley.

A divided Kashmir, without Kashmiriyat, is easier to rule. Why hasn’t the government instituted Vaapsi, in all these years? With all that might that once unified 560 princely states after independence, has in the past stifled insurgencies and has launched a space shuttle…? A divided Kashmir breeds separatist populations in the Valley, and separatism plays nicely into the narrative that justifies militarisation. A divided Kashmir has punished Pandits, leaving them resentful and conveniently disillusioned enough to lump in with the majority Hindu India, yet dispersed enough to ignore their need for the homeland they deserve. Conforming to an Us vs Them binary has facilitated repeated, ineffective administrative responses without any true pursuit of Vaapsi. Kashmir cannot survive without India because of cultural trauma and political incompetence, yet it cannot thrive as long as it is in this limbo.

The expectation that the periods of relative stability in Kashmir after 1989 are reason enough for Pandits to institute their own return exposes the extent to which their loss is misunderstood, minimised and negated. Whilst there are displaced families that have chosen to return during these times, collectively, the community remains unwilling to subject themselves to the possibility of being rejected by their homeland once more. As with any trauma, healing has to occur, and a simple geographical return is insufficient.

Upon realising the person they are talking to is Kashmiri, people will often exclaim it is “Heaven on earth”. Kashmiris, Pandit or not, residing in the Valley or not, are constantly reminded of their “heaven” by those who see its scenic beauty as just that-a physical environment. What is heaven to some, is both heaven and home to the Kashmiris, a home that has been ravaged by political-national-militant-human-rights-is-there-a-foreseeable-end struggles. The problem with Kashmir is reduced to whatever is convenient to the outsider- a doomed, “heavenly” destination, a “terrorist” hub, “militancy” or an independence movement. The diaspora’s lived reality is one which constantly rejects this simple description, a reminder that their traditions and culture endure even when the physical descriptions do not. Resistance comes in many forms, and an outsider cannot categorise the traumas endured by those in the Valley. Kashmiriyat cannot be erased as Pandits, and Kashmiris more broadly, will not allow themselves to be forgotten.

Just writing this story is my own way of reminding you that my community will endure, and our stories will survive.