‘The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles, but to irrigate deserts’

C.S. Lewis, 1943[1]

‘Through the My School website we have for the first time developed a national index of socio-educational advantage for every school in the country that allows us to compare apples with apples when we are talking about education’

Julia Gillard, Federal Minister for Education, 2010[2]

‘We have no desire to go back to the primitive conditions of the stone age. We ask you to teach our children to live in the Modern Age, as modern citizens. Our people are very good and quick learners. Why do you deliberately keep us backward?’

Aboriginal manifesto – 26th January, 1938[3]

‘Growing up as an Aboriginal child, looking into the mirror of our country…your reflection was at best distorted and at worst non existent’

Linda Burney, NSW Shadow Minister for Education, Shadow Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, 2007[4]

On 16 February 2016, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull delivered the annual ‘Closing the Gap’ speech to parliament. As he spoke he highlighted the ongoing struggle faced by Indigenous Australians, stemming from engrained systematic inequalities that are seeded and perpetuated by colonialist bureaucracies. Turnbull elaborated, ‘we have not always shown you, our First Australians, the respect you deserve. But despite the injustices and trauma, you and your families have shown the greatest tenacity and resilience.’[5] Though able to recognise the damage colonialism has done in the past, the Government continues to fail Indigenous students in its education policy. As Brazilian pedagogical theorist Paolo Friere wrote: ‘to affirm that men and women are persons and that a person should be free, and yet do nothing tangible to make this affirmation a reality, is a farce.’[6]

Australia’s colonial history is pervaded by injustice, and successive governments have implemented policies designed to subjugate Indigenous peoples. The White Australia policy is an obvious example, proclaiming in 1937 that: ‘this conference believes that the destiny of the natives of aboriginal origin…lies in their ultimate absorption by the people of the Commonwealth.’[7] Such policies were designed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Western culture. A missionary and prescriptive education system was seen as the only option for ‘success’ in society. This attitude stemmed from a notion of philanthropic racism – the belief that Indigenous cultures and pedagogies constituted some form of ‘savagery’ which the Western man needed to ‘save’ them from. ‘The capability of education to minimize…the student… to stimulate their credulity… serves the interests of the oppressors.’[8]

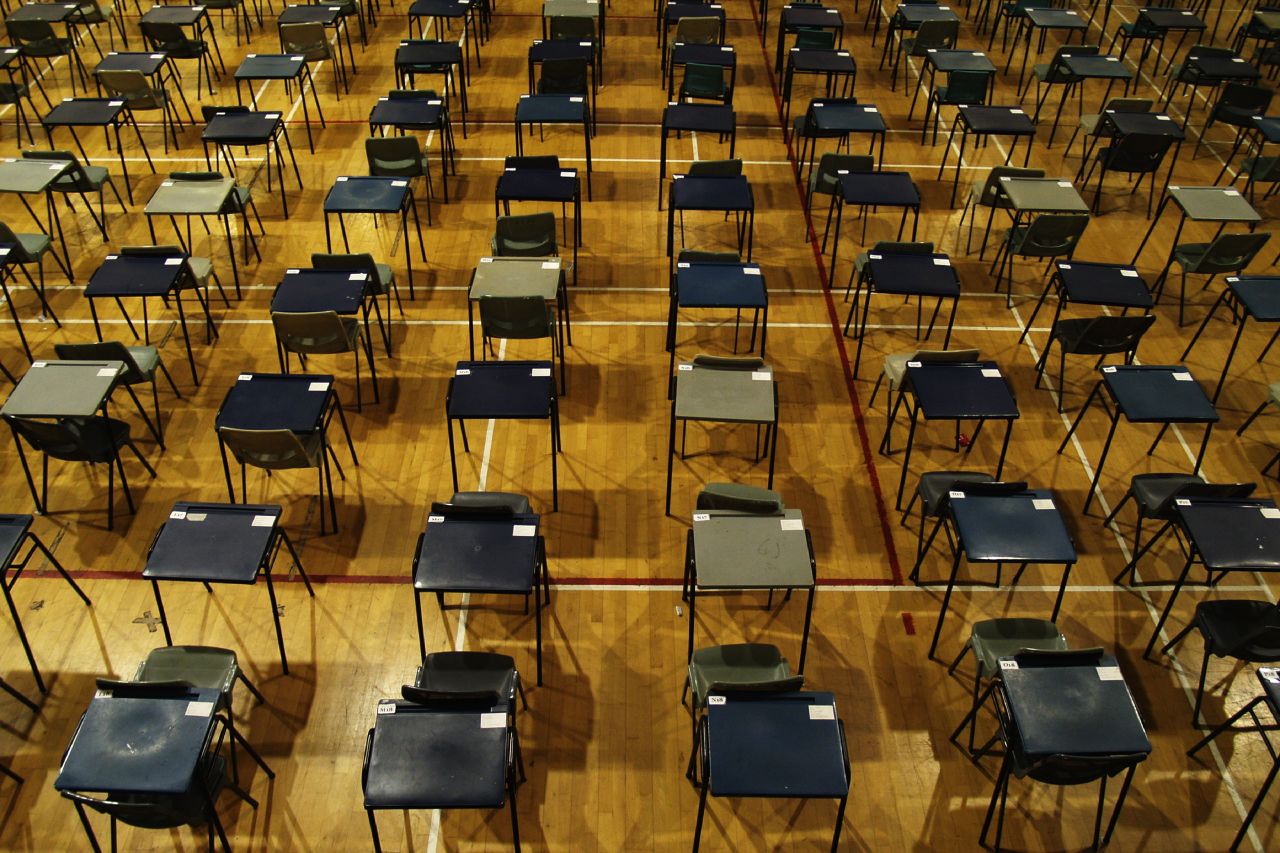

Of late, there has been a shift from such blatant paternalistic policies of assimilation, such as the White Australia policy. Instead, Australia has seen a more subtle perpetuation of the notion that success in Western terms is the only valid success. In 2010 the Gillard Government launched the controversial My School website, piquing the curiosity of concerned parents across the nation. My School allowed for a side by side analysis of all schools based on literacy and numeracy data, the socioeconomic level of students, and financial expenditure, among other factors.[9] The website served to fuel the increasingly competitive nature of Australian schooling, categorising certain schools as ‘more desirable’ than others and perpetuating disadvantage in the education system.

The issue posed, then, is this: how can such an institutional system be reconciled with the complex requirements of successful and diverse Indigenous education? Should the government attempt to integrate Indigenous people into a system of oppression, rather than transform that structure so that they can become beings for themselves?[10]

The implementation of such a standardised education system posits a challenge to Indigenous education, whereby Indigenous education is added as a side program to the regular curriculum — a ‘bolt on’ approach.[11] A de-personalised, statistic-based program is incongruous with a culture that has traditionally espoused an education based upon oral tradition and cultural engagement. When imposed by the oppressive class, education can serve as an instrument of internal colonialism as it socialises the colonised into an acceptance of inferior status, power and wealth. This was seen clearly in the White Australia policy that held English as the dominant language of teaching and that dismantled Indigenous power structures. The ‘white saviour’ attitude that permeated policy saw children removed from their families and educated in a way that fit colonial values and viewpoints. Friere argues that oppression can only be overthrown through an authentic pedagogy, not one ‘carried on by “A” for “B” or by “A” about “B” but rather by “A” with “B”, mediated by the world – a world which impresses and challenges both parties.’[12]

In his submission to parliament, Professor Bob Morgan of the Wollotuka Institute argued that the flaw in the Australian Government’s National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy is that it is largely concerned with matters of educational access as opposed to educational transformation.[13] To simply facilitate financial arrangements between the Commonwealth and state education providers is not sufficient for achieving the desired outcomes. These programs are ‘couched in terms that promote an illusory and profoundly flawed homogeneity amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and thereby deny the depth and richness of diversity that exists in and between Indigenous nations.’[14] If an education plan is designed ‘according to [the oppressor’s] personal views of reality, never once taking into account (except as mere objects of their actions) the men to whom their program was ostensibly directed’, they will fail.[15] Change will not occur in Indigenous Communities unless governments allow for local ownership of change. Langton argues that Governments should provide the resources for Indigenous communities and families to form partnerships with their local schools so that academic standards can be improved and facilitated.[16]

Indigenous cultures place paramount importance upon oral tradition. The imposition of testing-based Western literacy and numeracy systems immediately puts Indigenous students at a disadvantage. Today, 30% of Aboriginal adults lack basic literacy skills and there is a consistent disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students when it comes to meeting national standards for spelling, grammar, and punctuation.[17] When funding is tied to achievement, an inability to reach benchmark goals in tests such as NAPLAN (as was proposed by Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews)[18] can mean Indigenous students are not granted opportunities which could contribute to breaking the poverty cycle, such as admission to university and other tertiary programs.[19] Thus, Indigenous communities are posited with a unique dilemma: how to preserve culture whilst also allowing students’ success by Western standards? Professor Morgan raises the notion of the ‘guest paradigm’– the experience of Indigenous students who are uninspired by ‘Eurocentric’ education systems which have served to marginalise them.[20] Engaging in a curriculum written from a dominant perspective perpetuates the silence of the disadvantaged as cultural identity and language is not embedded in the formative education of these students.

As is evident from the importance of oral tradition, much of Indigenous culture is embedded in the nuances and complexity of language. How can a holistic education for Indigenous students be achieved if it is only taught in a colonial tongue? How can Indigenous students be expected to compete with non-Indigenous students when for the majority of them English is not a first language but rather an additional language.[21] The policy of bilingual education was introduced by Former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. Yet, until 2009, less than 20% of remote Indigenous schools offered bilingual classes.[22] Furthermore, at the end of 2008 the Northern Territory Government (with support from the Commonwealth Government) determined that the language in which the first four hours of class must be taught for every day ‘must be English.’[23] To educate Indigenous students primarily in English means they are forced to adapt to a Eurocentric way of thinking. This creates a situation in which an education system is entirely misaligned from cultural experience, promoting disengagement in students. Utilising policy to fund bilingual schools would help to undercut the ‘notion of treating Aboriginal people as guests in the dominant educational domain’.[24]

How can a child be inspired to learn when their curriculum glosses over their cultural experience? When the providers of their education do not speak to them in their language? The Indigenous education problem is a result of the perpetuation of imposing Western structures upon Indigenous society. If we want to see the disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous education standards diminished, then we must truly attempt to create an inclusive pedagogy. The mobilisation of a disadvantaged group against their imposed oppressive structures can neither be done solely by the marginalised, nor be prescribed by the oppressors themselves.

Bibliography

[1] Lewis, C.S. (1943) The Abolition of Man, Or, Reflections on Education with Special Reference to the Teaching of English in the Upper Forms of Schools. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

[2] Gillard, Julia. MP (2010). Address to the Sydney Institute: A Future Fair for All, School Funding in Australia.

[3] Mesnange, Gisele (1938). Statements from the Aborigines Progressive Association. Transcript, 2010.

[4] Gibson, Joel and Pearlman, Jonathon (2007). When I was fauna: citizen’s rallying call. Sydney Morning Herald

[5] Gordon, Michael (2016). Closing the gap and learning the language. Sydney Morning Herald.

[6] Friere, Paolo (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed

[7] Anderson, Michael (2015). Can an Aboriginal School break the vicious circle?. Creative Spirits.

[8] Friere, Paolo (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 22.

[9] Harrison, Dan (2010). Rich or Poor? Gillard plans to put it all online this year. Sydney Morning Herald.

[10] Friere, Paolo (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 23.

[11] Ferrari, Justine (2014). Marcia Langton: ‘bolt on’ system a let down.

[12] Ibid. 35.

[13] Morgan, Bob (2015). A submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Indigenous Affairs Inquiry into Educational Opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.

[14] Ibid. 4.

[15] Friere, Paolo (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

[16] Ferrari, Justine (2014). Marcia Langton: “bolt on” system a let down.

[17] Creative Spirits (2016). Aboriginal culture – Education – Aboriginal Literacy Rates.

[18] http://theconversation.com/naplan-data-and-school-funding-a-dangerous-link-46021

[19] Creative Spirits (2016). Aboriginal culture – Education – Aboriginal Literacy Rates.

[20] Wakatama, Giselle (2016). Newcastle academic slams ‘Eurocentric’ education for Indigenous Students.

[21] Creative Spirits (2016) Too little Aboriginal Bilingual Education.

[22] Devlin, Brian (2009) Bilingual education in the Northern Territory and the continuing debate over its effectiveness and value.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Wakatama, Giselle (2016). Newcastle academic slams ‘Eurocentric’ education for Indigenous Students.