In October 2013, students and staff at the University of Hawaiʻi painted this mural on their campus in Honolulu. The mural was painted in protest of the University’s involvement in plans to build a thirty-metre wide telescope on Mauna Kea, a very sacred place for indigenous Hawaiians.

This mural captures a moment in which students and staff call their institution to account. Their demand that the University operate as a “Hawaiian place of learning” reveals an implicit obligation for their institution’s administration to not just respect the indigenous people on whose land their campus lies, but to integrate their ways of knowing and being more deeply into everyday campus business.

The University of Hawaiʻi has a history of politically-engaged scholarship on Hawaiian history and culture. Activists claim that it is hypocritical to create research and teaching problems learning about Hawaiian culture, but then fail to truly ‘walk the walk’ in terms of how they engage with the community.

We might compare this to a university teaching the horrors of colonial exploitation of Africa but still hosting a statue of Cecil Rhodes, or a university researching climate change yet holding shares in fossil fuel -related industries.

United under a banner of decolonisation, scholars and students across the world are demanding that those who talk about the enduring legacies of colonial histories also examine their complicity in these systems, and work to dismantle them. Essentially, decolonising academia is a project to restore reflexive integrity to what happens in universities: it’s not sufficient to talk about critical theory if you do not animate it.

Pacific Islander scholars have made significant inroads to enacting such integrity. Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s pioneering book Decolonizing Methodologies asked researchers of human culture to consider the problematic symbiosis of social science research and imperialism.

These arguments cut a cogent line through the troubling history of social science’s engagement with indigenous people. Compelling as they are, however, enacting their praxis-based imperatives is a difficult task. To examine exactly how scholars go about decolonising their work, I’m researching the Pacific Studies academic community.

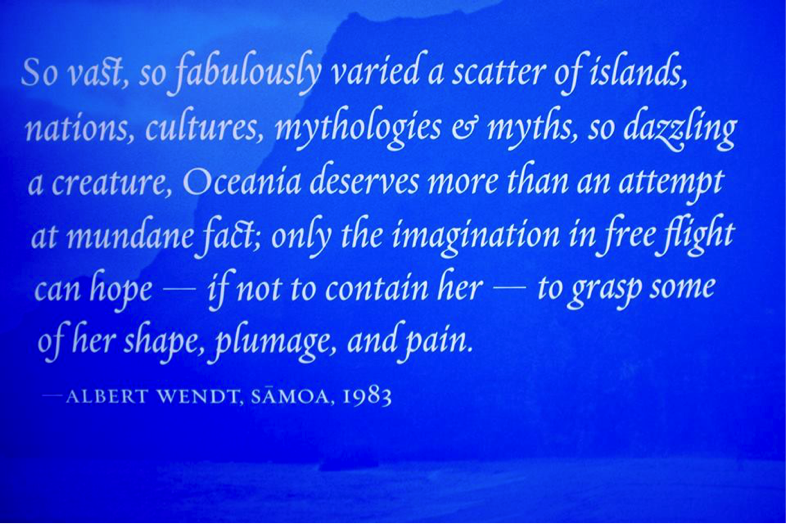

Pacific Studies – a culture/area studies hybrid with a deeply decolonial orientation – has offered a surging seascape of methods, if you’ll allow me the metaphor. In the Pacific, a region so often dismissed from Australia as being too irrelevant to our big-continent interests, scholars have engaged in stunning creative and intellectual risks to produce decolonised knowledge. In this field, it is normal to use oral history techniques and collaborative ethnography to collect information; to take seriously elements of lives like gossip, humour, superstition, art or sport; and to communicate research findings in ever-creative mediums. Albert Wendt, a Samoan writer and academic, justified this approach as such:

Perhaps it is tempting to dismiss such creatively-engaged research as being too reliant on so-called ‘soft humanities’ methods. But decolonisation’s power should not be underestimated: as an idea, it is resilient and flexible enough to be applied to a very wide scope of human activity, illuminating power dynamics and uncomfortable realities of practices that seem, perhaps, impenetrable to colonial legacies. For example, Bani Amor writes a blog about the need to decolonise travel. Decolonial Atlas upends our assumptions about cartography. Clare Land’s book Decolonizing Solidarity urges a reflection on the ways that even practicing solidarity with indigenous people can be a site for re-embedding of colonised dynamics. The list goes on.

So how do we decolonise the constituent practices that make up academia? Let’s take, for example, teaching. Teaching is a core academic activity for most scholars: it allows research to be spread, ideas to be discussed, careers to be nurtured, and vitally, income to be raised.

It’s also a site of some very problematic dynamics. Critical pedagogy asks us to look at how societal power structures are replicated in classrooms and perpetuated by what we teach and how we teach it. In the case of the Pacific – and Australia, for that matter – we need to ask about the presence (or lack thereof) of indigenous ways of knowing, and how diverse ways of learning are accommodated. Too often social privilege systems are reinscribed by affirming only white, male, and/or colonial stories about the world.

So, what does a decolonised classroom or curriculum look like? When I imagine a decolonised classroom, some of my own experiences come to mind. My own experiences in Pacific Studies has had some of the following highlights: I’ve learnt about the history of Micronesian navigation by sanding down a canoe, about where to pick edible seaweed through a hula dance, about the connections between food security and sovereignty by helping to build a sea wall, and about the spiritual significance of the taro plant by getting dirty in a garden.

For me, a decolonised classroom is one that perhaps isn’t a room at all – it’s a site in which students access corporeal or embodied communication modes as much as text-based ones, in which lecturers learn as much as students, emotional states are altered and acknowledged, and most importantly, the community from whom we learn is engaged, respected and made visible at all times.

It’s been my experience that changing the way that I learn and teach unsettles the usual expectations of a classroom to the extent that learning about culture, history and society begins to dismantle assumptions that don’t serve a decolonised vision. We make space for ways of knowing the world that don’t translate into linear or logical reasoning, creating knowledges that cannot be easily pummelled into chunks of dry text. Students are put into situations where their own participation in settler colonial systems is revealed and challenged.

Of course, teaching programs are never without problematic aspects. They always rely on a limited set of knowledges communicated in a limited number of communicative modes, for purposes of sheer expediency. They almost always limit access to those privileged in some form. And yet perhaps, as we move ever closer towards the huge goals that fuel decolonial visions, we can enact tiny interventions to chip away at colonial systems. Perhaps that looks like changing a curriculum, supporting a community engagement program, or holding your institution to account in some way. If we have the privilege to operate within a university system, then we have an obligation to ask that our institution is a place of learning that actively serves the communities it researches.

Images by Bianca Hennessy, taken at the, taken during the Pacific Islands Field School in O’ahu, Hawaiʻi.