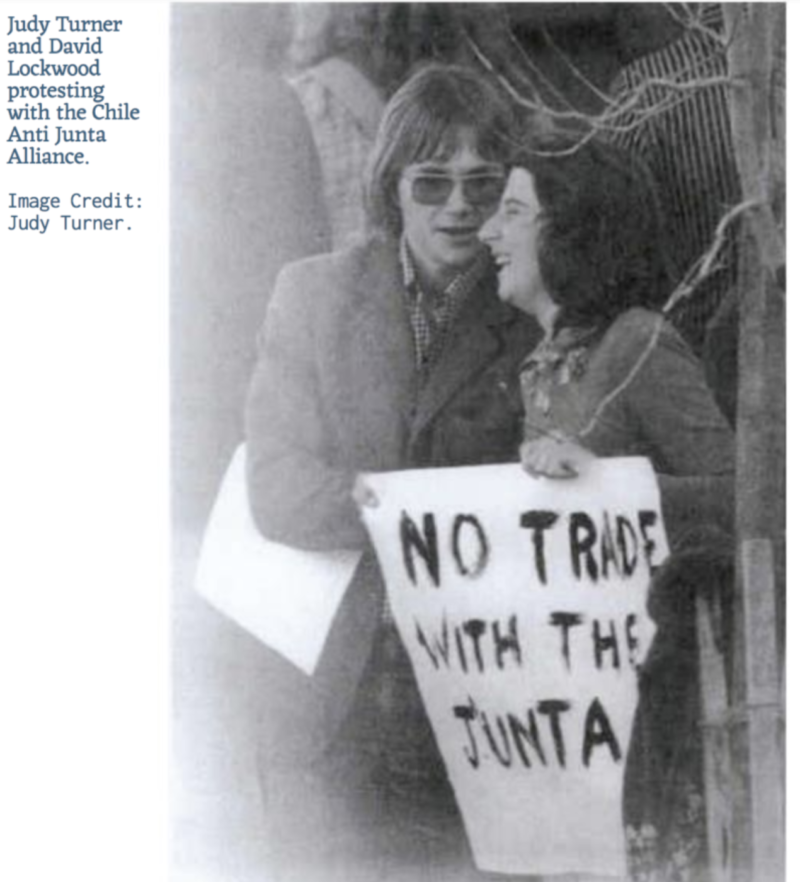

This is just one of many stories Judy tells me from her days as an undergraduate student at ANU from 1971-1974, when she devoted far more time to activism than to her formal studies. She was involved in the major ANU activist group at the time: the ANU Labour Club (not connected to or to be confused with the Australian Labor Party), an anti-capitalist activist group that organised heavily in the ‘60s and ‘70s on many progressive causes. These causes included fighting against the Vietnam War, South African apartheid and the Indonesian occupation of East Timor, campaigning for low-cost accommodation at the ANU and the democratisation of the University, and supporting Aboriginal land rights activism.

The ANU Labour Club

Judy recalls the ANU Labour Club gaining momentum after the 1971 Day of Rage, a demonstration Clive Hamilton describes as, “a rambunctious protest by university students against just about everything.” For Judy, the protest was intended as a message from students across the nation that students did not like the world they were about to enter into as adults. From then on, she says choosing campaign issues was almost like choosing university courses. While their campaigns were undoubtedly dictated by their context, they would have group meetings to pick their campaign focus for the year.

Identity and Anti-Racism

In a surprising synchronicity, Judy and I discover that both our families were Jewish communists from Eastern Europe. Her family’s left-wing background gave her an early interest in anti-capitalist struggles. Yet, in terms of her engagement in fights around anti-racism, such as anti-apartheid campaigning, it is not her Jewish background she singles out, but rather her years growing up in Papua New Guinea and witnessing racial discrimination there, that she says instilled in her a concern for the pernicious violence of racism.

Judy conveys that she had a strong awareness of the importance of knowing her place in activism— of listening and learning from those whose struggles she sought to support, rather than attempting to lead or take ownership of the issue. She describes her involvement with the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, and recalls the ANU Labour Club responding to a call from them for bodies on the ground to defend the Embassy against police demolition. The group saw themselves as “shock troops”, as the frontline there to face down police. She recalls, “we were kind of like hired muscle, we were pretty aware it wasn’t our struggle but we were sympathetic to the cause and prepared to go and offer support.”

Trawling through online archives, I find an article Judy penned at the time, responding to what she perceived to be a smug and ignorant portrayal of student support of the Tent Embassy. She decries the patronising tone of the original author in claiming student credit for Aboriginal activism and writes that “the students were … aware at all times of the need to be followers not leaders, and of the fact that they were mere appendages of the black movement.”

While discussing her anti-apartheid activism, Judy frequently repeats the adjectives “fun” and “clandestine”. She describes the “mock-guerrilla” activities they engaged in to disrupt everyday events, including having a load of sand delivered to the South African ambassador’s driveway. Etched into her mind is the less enjoyable, yet nonetheless exciting memory of camping outside the South African Embassy in the biting cold of the mid-winter Canberra as part of a constantly manned vigil that lasted several months.

O’Connor’s Agitprop

Epitomising the creativity and fun of the ANU Labour Club, Judy tells me of the DIY, activist printing studio they operated out of her share house on Nardoo Crescent in O’Connor. At the time, several share houses filled with ANU Labour Club students operated as bases for organising.

The house at Nardoo Crescent belonged to Judy’s parents and was Judy’s home for much of her childhood. In their garage, the group designed and printed posters and merchandise to promote their demonstrations and causes. Judy remembers one student, Mark Horridge, designing particularly striking posters in the garage, which the rest of the group would then help to print.

One aspect of the printing press Judy enjoyed most was pasting the posters across Canberra — an activity that was illegal at the time. Judy describes this as a “cat and mouse game” with the police. She doesn’t recall ever being arrested for postering, but does remember occasionally being asked to take down images.

After postering, she recalls, “You’d come back at two or three in the morning and be totally exhausted but you’d have this sense of accomplishment that you got away with it and outwitted the police, then everywhere you went in Canberra you’d see the results of your work.”

Speaking of the excitement and joy of activism, she recalls, “It was our version of the 60s in a way. There were personal and political freedoms, there were people experimenting with drugs … it was all mixed up as a young person’s adventure in Canberra.”

Comparing her experience of university with students today, including her own five children, she believes there was less at stake when she studied. Speaking of her decision to repeatedly risk arrest and confront police during protests, she says students weren’t thinking much about how their involvement might impact on their future careers. Compared with students now, she notes that she and her peers were mostly on scholarships and did not pay fees at university. She wisely observes that it is, “somehow easier to be hostile to the system when the system’s supporting you than when it’s not”.

Despite emphasising the social and enjoyable nature of her activism, Judy highlights how firmly she believed in the causes. When I ask Judy if she has any regrets from her time involved in activism, she reflects that being so dedicated to the causes came at a detriment to her own studies. “Do I regret anything? Yes, I regret not putting more time into my studies. But at the time the social aspect was so important to me, and I think to many women. It felt more important to put effort into the things the movement dictated than to my own study.” She perceived the men as better able to juggle their studies and their activism, often doing more theorising, while the women seemed to do more of the practical organising. She says the women tended to more readily put their own work second.

The Political Becomes Personal

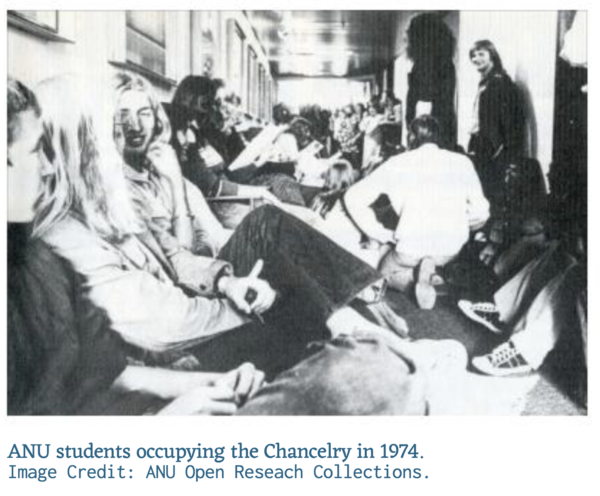

She tells me she also regrets the group decision to concentrate energy on internal campaigning against the University. During 1974, the ANU Labour Club campaigned for student ownership of the ANU, including control of management and assessment. The campaign pushed to abolish exams and established an unofficial 10-10 committee—ten students and ten academics to manage the University. In April of 1974, Judy was one of hundreds of students who occupied the Chancelry. With both her parents being history academics and faculty members of the ANU, Judy found this personally awkward, but also felt that the campaign unnecessarily alienated previously sympathetic academics. She reflects, “we sundered some of those relationships with the academics … A lot of my parents’ friends were appalled that we had turned our attention to something so benign as the University. We’d started seeing the University as the oppressor, which was kind of naïve of us I suppose.”

The ANU Labour Club Today

I ask Judy whether she is still in touch with anyone from the Labour Club. Remarkably, she tells me she remains friends with almost everyone from those days. Today, Judy works in fundraising for NGOs, and spent several years after university with Amnesty International. Many others from the group, she informs me, have become academics (who the ANU Labour Club had once pejoratively referred to as “accas”.) A few went on to spend lives in activism. Reflecting on student activism today, Judy feels inspired by the activism she sees students engaged in, while acknowledging campuses no longer occupy the central role for activism they once did.

Anna Himmelreich, in her piece in this edition, cautions against romanticising or mythologising student activism from the ‘70s, arguing that student activism has never occupied a central place for the majority of students at the ANU. Despite this, I leave my interview with Judy wondering what it would take to return the spirit of the ANU Labour Club to the ANU today. Looking at most university campuses across Australia today, it is difficult to imagine hundreds of students occupying the Chancelry in a fight to democratise the University, or to imagine droves getting arrested opposing neo-imperialist wars. Whereas many students once fought against occupation in East Timor, few at the ANU today seem aware of the role our own Chancellor, Gareth Evans, played in supporting Indonesia as Australia’s Foreign Minister. Perhaps in learning the activist history of our campus through people such as Judy, at the precise moment when the ANU erases by demolition the key sites of that history, we can begin to imagine a future of the ANU as a site of engaged, creative and critical activism at the scale of excitement of the ‘70s.