Professor John Buchanan is the Head of the Discipline of Business Analytics at the University of Sydney Business School. From 1979-1984, he was an undergraduate student of History and Law at the ANU. During that time, he helped establish the ANU Left Group, a large group of non-aligned anarchists, communists, and socialists. Along with others, he was a founding member of the Law School Action Group – an alliance of independent socialists and small ‘l’ liberals – that controlled the ANU Law Students’ Society from 1982–1985.

OS: How did you first become involved in activism?

JB: My parents were Presbyterian Christians who started from the notion that if people are poor, it’s not their fault. They had voted Liberal in every election until 1972 – but never voted Liberal after then. Throughout their lives they’ve had a deep commitment to making the world a fairer and more caring place. When I did a history essay in year nine I learnt about social justice and I broke with the family tradition and became pro-ALP [Australian Labour Party]. The next year the Whitlam Government was sacked and I kind of lost faith in parliamentary democracy and looked to alternatives. I was part of the first intake into the ACT Secondary School College System. Teachers and school administrators encouraged us to form an independent student council. At Narrabundah College students were interested in direct as opposed to representative democracy and our union was based on weekly general meetings of students. During this time anti-uranium activism was big and Friends of the Earth had a big libertarian socialist and anarchist presence. I picked up my politics from those people. When I came to ANU I was somewhat disappointed because we actually had a better mobilised secondary student population than the University population at that time.

In first year, I helped organise the Campus Environment Group, but in second year there was a libertarian-socialist elected chair of the Students’ Association, Louise Tarrant, and she wanted to get all the different left forces together. There was a very strong feminist group then, there were the environmentalists, there were left ALP people. There was quite some disenchantment about accessibility of affordable housing as well. We coalesced in a general group called the Left Group.

OS: Do you have any particularly strong memories from the ANU Left Group?

JB: As a representative of the ANU Left in the early 1980s I debated Julia Gillard over the course of number of Australian Union of Students (AUS) Annual Councils. Gillard’s line was to get everyone to go to university. Our position was, “education for what? What’s the point of getting people to go to university if they’re just being cranked through or seeing education in purely instrumental terms?” I’ve modified my position since then in light of changing circumstances, but still remain committed to engaging with the content and quality of education — not just its quantity.

Gillard, however, remained fixated on increasing “education participation”, indifferent to its quality and wider ideological and cultural significance. Her policies about “demand-driven” growth funded by student debt have really strained the university system and all but destroyed quality vocational education.

OS: At least, that’s what you say in public?

JB: [Laughs] No no! I’m still strongly a socialist, but over time I’ve developed great respect for pluralist forms of liberalism.

OS: Can you tell me a bit more about your ideological grounding?

JB: My vision of socialism is about creating a world where it’s easier to have friends. That will ultimately require a far fairer distribution of income and far more inclusive and sustainable ways of organising the means of production, distribution, and exchange.

The politics where I started off were out of a libertarian socialist tradition, which is commonly referred to as anarchism or syndicalism. I was particularly influenced by G. D. H. Cole’s notion of guild socialism where you could only achieve a fairer society if you had a majority in parliament, but that majority had to be supported by mass democratic organisations beyond parliament, particularly in the economy. That’s why it was known as guild socialism — workers organised through collective organisation which shaped production, not just parliament itself.

My first degree was in history and I majored in the history of revolutions. I’ve gained an appreciation that you have to harness all people of good will interested in a progressive outcome and they mightn’t be socialists, they might have other outlooks. You need an organisational form to harness a plurality of forces. The people who’ve thought most about that issue tend to be liberal collectivists like Keynes and Beveridge.

OS: I found it interesting that you said the ANU Left Group combined communists, socialists and anarchists. How did that work in practice? Was there sectarianism?

JB: We were all anti-capitalists. We all had a strong, agreed commitment that you had to get beyond the world that sees people either as threats or opportunities because it’s a terrible way of thinking. That was a unifying force, and it didn’t really matter if people were anarchists, communists, left-wing social democrats, or even social liberals.

If there was a tension it wasn’t on sectarian lines, it was more on the degree to which you theorised your practice. I was on the intellectual reflection side, we used to call the other side ‘mindless activists’. They called us ‘academic wankers’. It wasn’t vehement or debilitating but it was a tension.

OS: It didn’t matter if some believed in the need for a violent overthrow of capitalism?

JB: The Communist Party of Australia was going through its euro-communist phase which was very much about mass democratic class struggle. There were some Trots but they were marginal – there were the International Socialists but there were only ever about six or seven of them and they didn’t work that closely with us.

OS: How did you translate your strong ideological basis into practice? For example, were you using consensus decision making?

JB: There was a very strong libertarian streak and some of the Leninists got pretty pissed off with that. We had a kind of, ‘dictatorship of the activists’ — if you did the shit work you got to decide the policies. If you made the posters you got to decide what went on them. That was a bit silly — simply because you’ve got time to make a poster doesn’t mean that you should be speaking for everyone in the group.

We did make most decisions by consensus. We’d meet weekly and amongst the Left Group you’d never have less than ten and normally you’d have 2025 people. There were specific campaign groups, so my friend Bill Redpath and I were in the education collective, Ed.Coll. There were also Accommodation and Peace groups. Left Group was an umbrella, we got together for things like Student Association elections and AUS.

When the organisation worked the best was when AUS was under attack in 1982. The Left Group formed the Friends of AUS group, we had an information committee to figure out our line, a campaign committee and an activist telephone tree. It was at least 75, it might have been 100, who were involved in the campaign consistently over the six weeks. We ended up winning that campaign by a margin of 60/40 on a large voter turnout. This was at a time when the Australian Liberal Students Federation successfully campaigned for several campuses to disaffiliate from the AUS.

OS: What is an activist telephone tree?

JB: We didn’t have internet or text – to get a message out you’d phone one person and they’d be organised to phone another on the tree. You might have five branches, so you’d only have to phone five and they would get the message out.

OS: Could you tell me a bit about how your education activism in the ANU College of Law began?

JB: When I started in 1978 a progressive group had already captured the Law Students’ Society, led by a guy called Michael Bozic. These people were very involved in the Redfern Legal Centre, Fitzroy Legal Service, and the legal centres movement. They were an inspiration, but they were more concerned individuals, they weren’t out to transform capitalism.

In my Honours year I did an Althusserian analysis of G. D. H. Cole’s history of thought [A History of Socialist Thought: Socialism and Fascism 1931-1939], which gave me quite advanced analytical tools to then turn on the Law School. At the end of Honours, Bill Redpath and I formed the Law School Action Group and we won the Law School Society elections. These were highly polarised elections because we ran on an explicit left program. Bill and I were clearly Marxists but there were also small ‘l’ liberals and ALP members. In Law Schools, there are always people who just want to make a lot of money and traditionally they had control of the Law Students’ Society, but we won those elections for four years in a row with voter turnouts that involved upwards of 40 per cent of the student population.

OS: What sorts of things did you do in the Law School Society?

JB: The first thing we did was to produce an Alternative

Law Handbook with genuinely alternative (i.e. critical) content. Until that point the handbooks had been chummy sets of essays put together by staff and students that celebrated life at the law school. We said you should have critique of the law, not just a celebration. We included critique on the law and legal education, and student commentary on each unit. After releasing our first handbook we were threatened for defamation. This was because we reported student feedback that noted the opinion of a number of students that one of the lecturers was leery and sexist. There was widespread opinion amongst students at the time that this lecturer had a terrible reputation for being sexist – teaching criminal law and being sexist while teaching laws around rape and things like that.

OS: I guess if any college will sue you…

JB: We had just reproduced what students said. We learnt later to say, “In the opinion of one student or several students…”. If we’d done that we would’ve been fine.

OS: What motivated your curriculum activism? I recently spoke with another former ANU student activist, Judy Turner, who mentioned regretting her involvement in education activism for being too narrowly focussed. Did you ever feel that way?

JB: We saw universities as playing a critical role in the reproduction of bourgeois ideology – that’s where we were coming from. Law Schools basically saw themselves as adjuncts to the profession and we wanted more than that.

If you look at what economics and political science departments have been turning out over the past fifty years – these are massively wasted opportunities in teaching people how to ask really useful questions. Political science now is all about game theory – what does game theory tell you about Trump? Most economists failed completely to understand — let alone predict — the 2008 global financial crisis.

I think a really close engagement with the intellectual enterprise of the university is important, but in a pluralistic way. We probably had the vision of the university being a ‘red base’ in the transition to socialism. Althusser and that school of thought was highlighting the importance of ideological and cultural struggle. Marxism provided ‘science’ as a way of seeing through the dominant ideology. If this could become widespread, universities could help make the world a better place. I’m more ecumenical now. I think the growth of new knowledge comes through reasoned debate and deep engagement with information and data — qualitative and quantitative. Institutions that do this are rare and universities are now under attack for doing just this.

OS: Were you inspired by critical legal theorists?

JB: Totally, we were looking at people like Duncan

Kennedy at Harvard and [William] Twining at Warwick. We had the Critical Legal Studies Reading Group. We were meeting fortnightly reading different essays. We got the faculty to pay for a series of discussion papers. For example, I wrote one on how the ANU Law School was dominated by a perverted form of legal positivism. That was an official Law School publication, it would be sitting next to where people picked up their compulsory readings for the week.

It was out of that culture that the Great Law School Show Trial emerged. It was a culmination of a whole lot of stuff we’d been doing.

OS: Can you explain the Great Law School Show Trial?

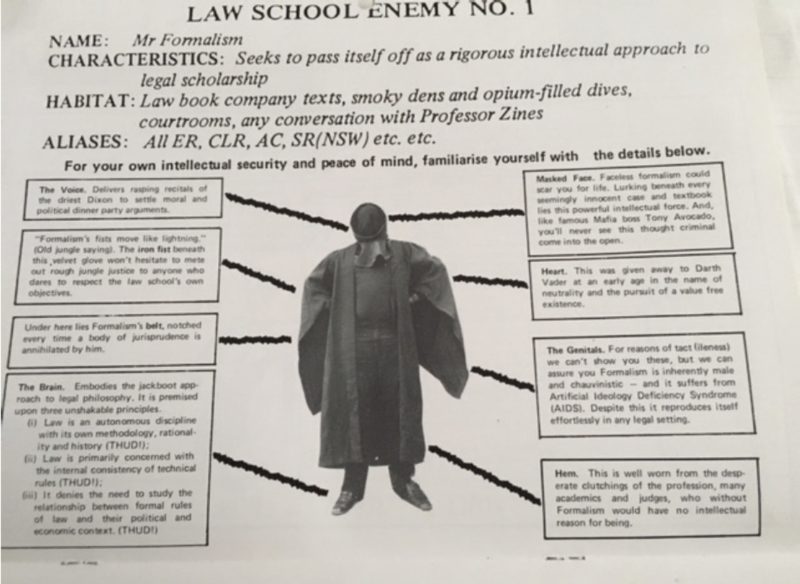

JB: As a group, we’d studied and been involved in the left for a while. One thing that was part of the left tradition was street theatre. The anti-uranium movement had used this quite a bit, the kind of, medieval, allegorical play form of demonising the enemy.

Being able to project what your enemy looks like was a lot of fun. We made legal formalism look like Darth Vader. Students would glaze over when we talked about perverted forms of legal positivism. They’d just say, “What the fuck are you talking about?” Whereas, you put a play like that on, it’s a way of explaining quite complex concepts in a concise and accessible way.

OS: When I was looking at online archives, I found an article describing you as an extremist. How did you feel about being a spokesperson and being personally exposed in that way?

JB: People used to laugh at that because, while I was an Althusserian Marxist, personally I was very influenced by G. D. H. Cole and he had this notion that he was a ‘sensible extremist’. The real problem was capitalism. Capitalism causes massive suffering and wrecks the environment. I thought, “You might call me extreme but I’m extreme for a reason, anyone sensible and concerned with these issues has to respond in the way we are”. Being called an extremist didn’t threaten me. My friends on the left just laughed because they always regarded me as one of the more mild-mannered of the group — a very strong adherent of alliance politics.

OS: Did your activism ever take a personal toll?

JB: Activism destroyed my first de facto marriage. We went out for seven years and bought a house together. I took my student activism into trade union activism. I got obsessed with the struggle for social justice and a better world. After I finished my Law and Arts degrees at ANU, I went back to do an Economics degree part time. If you study part time and are an activist, it doesn’t leave much time for anything else.

Activist culture can be very damaging to your personal relations. You can justify anything in the name of making the world a better place. I do regret not spending enough time with my friends and my lover. I’ve since taught myself mindfulness meditation – not because I’ve become a conservative but because destroying yourself won’t help the cause succeed.

OS: Do you maintain hope in the success of the causes you believe in?

JB: I’m still totally socialist. Capitalism does great things but, boy, it does really, really bad things too. I’m completely committed to making the world a fairer, more sustainable place. From where I sit now, universities are one of the few places where people still take ideas seriously, where rationality still counts for something. That’s the way I think I can help the cause. That’s not to turn universities into sites for socialism, but for them to be sites where people can think and question and generate new ideas and have them subjected to serious scrutiny.

OS: So, are you infiltrating the Sydney Business School or is it a sympathetic place?

JB: [Laughs] I’d say I’m a respected academic! Business schools have a reputation amongst some people as just being adjuncts to the business community, which is incorrect. Engagement with ‘industry’ is important. But ‘industry’ is defined very broadly to involve public sector organisations and NGOs [non-government organisations], as well as private sector firms. And within business schools there is a lot of critical literature.

I came in through the industrial relations field and built on the labour process, labour market segmentation, and critical working life traditions. If you’re in the business world and go into the business school, by in large you’re interested in ideas, not making money, so the fraternity isn’t instrumental. There’s a big constituency there that wants business — and those involved in managing the public and NGOs sectors — to think critically.