You could be forgiven for thinking, or even believing, that you have a say in decisions that impact your life because you live in a democracy. “I vote. Therefore, I have a say.” But what if you wish to have a say in a different, more profound way?

Participatory resource management (PRM) is making a steady, global rise to prominence as a means to engage people in environmental decision making. Could this concept act as a model for putting the people back into democracy, for creating a new concept of democracy that expands each citizen’s role beyond the obligation to mark a ballot paper? Recently, Tasmania has experimented with this idea through the Forest Peace Process.

Participatory resource management is based on the idea that all stakeholders who have an interest in a resource should take part in the resource’s management. Proponents of the approach argue that participation is a democratic right and helps to create democracy through shared decision-making. However, it is also widely acknowledged that it is often impossible to involve all stakeholders in participatory processes and compromises often have to be made.

Putting this aside, what happens when a participatory decision-making process does create an agreement, a decision or a way forward? Should governments implement and support the decisions of the citizens they were elected by? The Tasmanian government, it appeared in 2014, thought not.

Rewind to 2009, when the Tasmanian forest peace process began. This process was as an attempt to resolve the conflict between foresters and environmental conservationists over the harvesting of native forests in Tasmania. The goal was to reconcile the substantial environmental values of the state’s natural forests with the economic contribution that forestry makes to the state. The foresters were seeking secure access to wood supplies and an improved public image while environmental non-government organisations (ENGOs) were seeking to reserve land for the conservation of biodiversity and other environmental values. The process evolved between 2009 and 2013, with many ups and downs. Criticism and support from various groups waxed and waned with every press release.

Finally, success was achieved. A peace agreement was implemented in 2013, with the negotiated agreement being passed by Tasmanian Government. It added 500million hectares of forests to Tasmania’s conservation estate. The forestry industry was granted access to 137,000 cubic metres of sawlogs and compensation agreements were set out. This agreement was supported by the largest ENGOs and the largest industry producers. This was a bottom up, citizen-led reform. It was heralded as a positive step in reconciling a decades-old conflict, although some criticisms remained.

Admittedly, it had not involved all stakeholders at all stages of the process. For example, the talks were initially held in secret between the “big companies” and the “big ENGOs”.

However, the process was opened up after the initial meetings. The process then allowed the input of broad sections of society and improved relationships between stakeholders from all backgrounds and at all levels. This peace agreement represented a wholehearted attempt at compromise to meet society’s needs as a whole: environmentally, economically and socially. It seemed as if this deal, and its subsequent support by the government, could represent a new democratic process.

Fast forward to 2014. With a change of government, the peace process was dismantled. The new Liberal Premier, Will Hedgeman, argued that a minority should not be able to influence policy and practice. It was, in his eyes, the role only of elected officials to make such decisions.

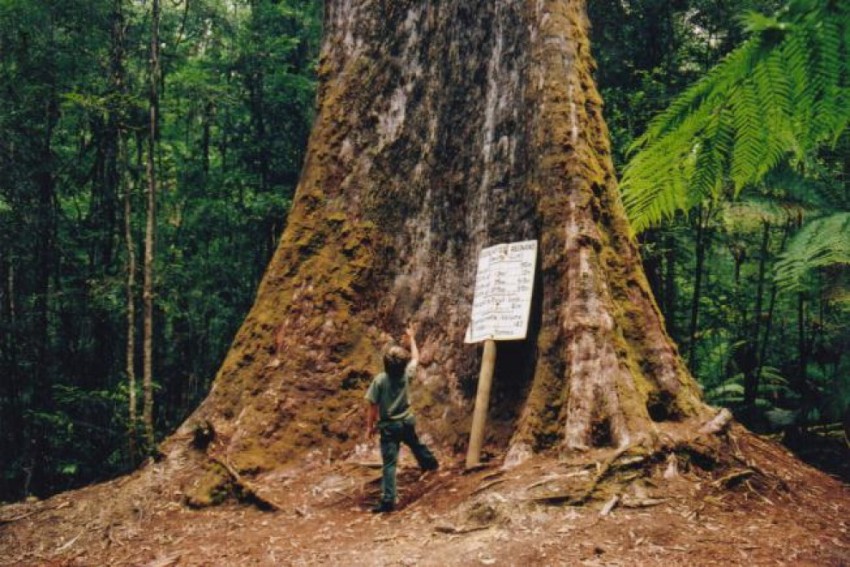

Although the repeal does not mean the immediate, whole-scale logging of the forest that was set aside for conservation by the agreement, much of that forests may now be logged in the future, as part of the Liberal government’s pledge to grow the forestry industry. Some “special species” are also now under more threat as the areas allocated to conservation by the agreement were chosen specifically to protect important species and expand the comprehensiveness of the Tasmanian forest reserve system. What the future holds for Tasmania’s forests is uncertain: the decision made unilaterally to uphold democracy – as in, ballot box democracy – has removed an agreement that gave multiple stakeholders some way to ensure the future of Tasmania’s beautiful, biodiverse and productive forests.

So what is democracy? Is democracy being able to elect someone else to make a decision for you, or is democracy being able to participate in making the decision for yourself? If governments can overturn decisions made by citizens, where is the democracy in that? Is it necessary that every stakeholder be involved at all stages?

These are all questions that have been asked before, debated time and time again. The Tasmanian forest peace process is just one practical example of an attempt to achieve a goal that simultaneously, perhaps inadvertently, created an alternative democracy. It follows in the footsteps of a world-wide shift towards community-based or participatory resource management. Emerging economies such as Vietnam are divulging their forest management to communities. Developing nations in Africa are benefiting environmentally and economically from community-based management. If there, why not in Australia, where democracy almost defines our national identity? Can shifts in the natural resource management paradigm be used to model wider implementation of more bottom-up governance? Not, I would argue, if it isn’t even given a chance. New creations are fragile and breaking them to pieces not only undermines the process of creating that object, but all future attempts to do the same.